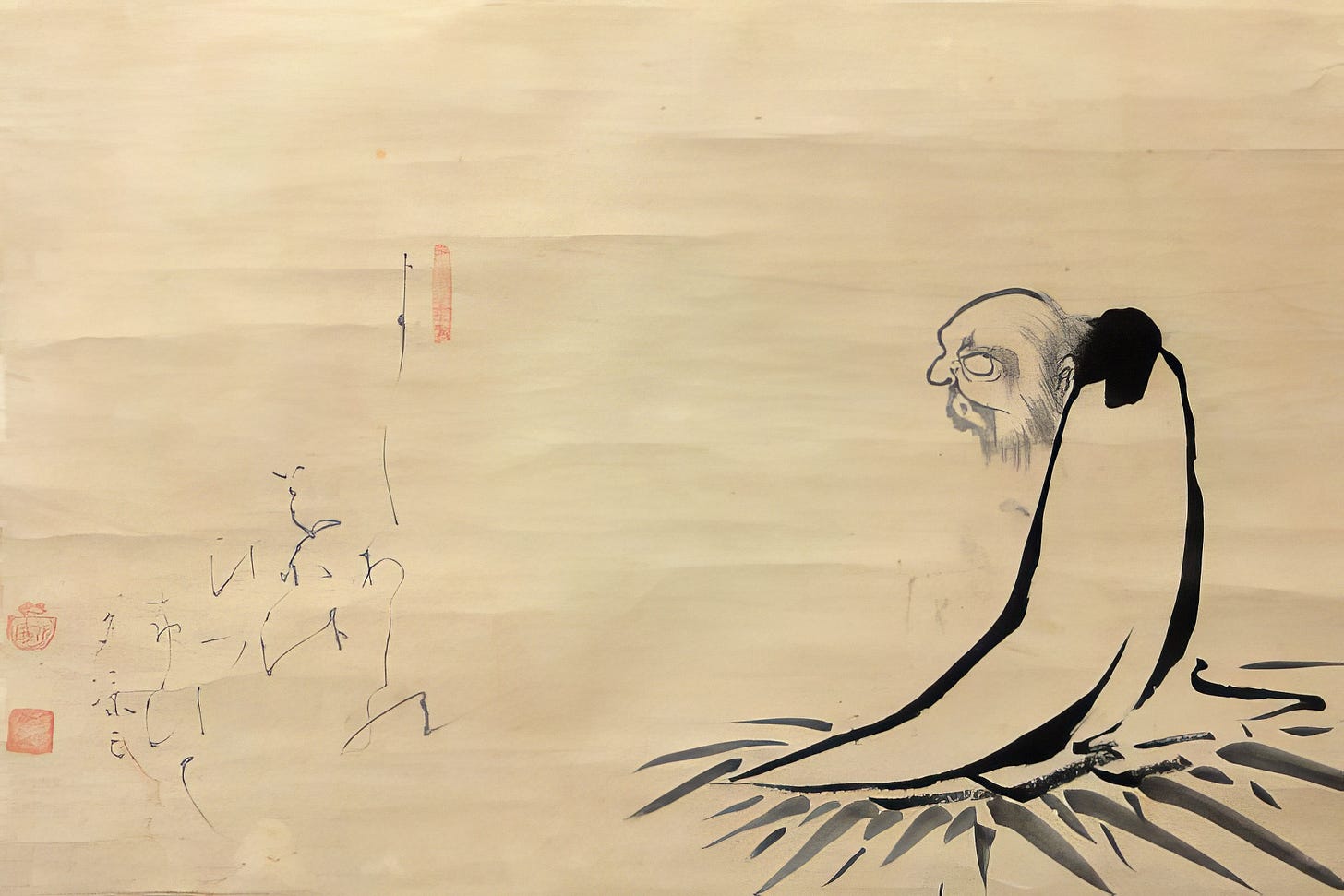

Hakuin Ekaku and the Revival of Rinzai Zen in Japan

Hakuin Ekaku’s Journey from Struggle to Zen Enlightenment

In this article, we explore how Hakuin Ekaku (白隠慧鶴), the Zen master who revitalized Zen in Japan, ultimately completed his enlightenment.

Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769), a profoundly influential Zen monk of the mid-Edo period, is regarded as the restorer of the Rinzai school. Originally, Rinzai Zen was one of the five houses of Chan Buddhism in China—comprising Linji (Rinzai), Guiyang, Caodong (Sōtō), Yunmen, and Fayan—and its influence extended across Japan, China, Taiwan, and Korea.

The Rinzai school was founded by the Tang Dynasty Chan master Linji Yixuan (?-867). In Japan, Rinzai Zen flourished primarily during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), largely due to the efforts of the Zen monk Eisai (1141–1215), whom I introduced in a previous article. Eisai traveled to the Song Dynasty, where he was deeply impressed by the tea culture practiced by Chan monks. He later introduced both Zen and tea culture to Japan.

As Zen Buddhism developed in Japan, it became organized into five major schools: Rinzai (臨済宗), Sōtō (曹洞宗), Japanese Daruma (日本達磨宗), Ōbaku (黄檗宗), and Fuke (普化宗). Over time, Rinzai Zen split into 14 different sub-schools. Even today, it is estimated that Rinzai Zen has approximately 1.98 million followers in Japan.

Rinzai Zen maintained a close relationship with the samurai governments of the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (1336-1573), whereas Sōtō Zen spread more widely among rural communities and commoners. During the Kamakura and Muromachi eras, Rinzai Zen wielded immense cultural and political influence. However, its dominance declined rapidly when the Ashikaga clan, the founders of the Muromachi shogunate, were overthrown by Oda Nobunaga.

After this decline, Rinzai Zen lost its power for some time, but it experienced a revival in the Edo period. The key figure behind this resurgence was none other than Hakuin.

The Arrogant Youth and the Path to True Enlightenment

However, Hakuin was not enlightened from the beginning. In his youth, he boasted, “No one in the past five hundred years has attained “satori (悟り, enlightenment)” as thoroughly as I have.” He was extremely proud and possessed a strong sense of superiority. He traveled across the country, engaging in fierce debates with monks and scholars, defeating them in arguments, and indulging in his own arrogance.

At the height of his conceit, Hakuin heard of an extraordinary Zen master. This individual was said to be living in seclusion in Shinshū (modern-day Nagano Prefecture). Intrigued, Hakuin immediately set off to meet him. This master was none other than Shōju Rōjin (正受老人).

Upon meeting Shōju, Hakuin attempted to challenge him in debate, as he had done with others before. However, Shōju shattered Hakuin’s arrogance with a single remark:

“You have only attained ‘Gakutokutei’ (学得底), the knowledge gained through learning. But if you truly claim to be satori, bring me ‘Kenshōtei’ (見性底), the realization of your true nature.”

To explain this in modern terms, “Gakutokutei” refers to the accumulation of intellectual knowledge—such as linguistic proficiency, expertise in social issues, or academic understanding of labor problems. This is a common trait among so-called intellectuals. However, Shōju saw this attitude as the real problem. Those who cling to “Gakutokutei” believe themselves to be superior, and society often reinforces this illusion of superiority.

On the other hand, “Kenshōtei” means elevating knowledge into wisdom that purifies one’s life. It is not about possessing knowledge for its own sake but about using it to unify one’s scattered thoughts and return to one’s true self.

This critique remains relevant even today. Many contemporary intellectuals should reflect on Shōju’s words. After all, mere intellectual superiority is one of the most despised traits in both Chinese and Japanese thought.

Struck by Shōju’s words, Hakuin underwent a profound awakening. He chose to become Shōju’s disciple and devoted himself to the rigorous path of Zen practice.

The Struggles of a Zen Seeker

During his training, Hakuin experienced a breakthrough when an old woman beat him with a broom. However, he later encountered another obstacle—he became obsessed with excessive ascetic practice, which led to a severe physical and mental breakdown. Later, he would refer to this condition as “Zen sickness”.

This phenomenon is not unique to Hakuin. Even today, many Western practitioners of Zen, especially those influenced by D.T. Suzuki, experience a similar crisis when they immerse themselves too deeply in Zen without proper guidance.

At this crucial moment, Hakuin encountered a mysterious hermit known as Hakuyūshi (白幽子), who lived in a cave deep in the mountains of Kyoto. Legend has it that Hakuyūshi had lived for several hundred years. Recognizing Hakuin’s distress, he taught him a secret method that allowed him to recover from Zen sickness. Under Hakuyūshi’s guidance, Hakuin not only restored his health but also deepened his understanding of spiritual practice by studying not just Buddhist texts but also Confucian classics such as the Zhongyong (Doctrine of the Mean), Laozi, and the Diamond Sutra.

Hakuin continued his rigorous practice, and at the age of 42, he finally attained full satori (enlightenment) upon hearing the sound of a cricket’s chirping.

It is said that Confucius once declared, “At forty, I knew my destiny. (四十にして天命を知る)” Similarly, Hakuin, after decades of struggle, finally realized his true nature in his forties.