Unveiling Kyoto’s True Heart and Its Forgotten Shifts in History

Why Kyoto’s Center Moved and How It Defines the City Today

In this article, we lay the groundwork for uncovering the true Kyoto, allowing you to experience Kyoto tourism more deeply than anyone else.

We have touched on Kyoto’s history in previous articles, but in today’s overtourism climate, it is rare to meet people who truly understand Kyoto’s essence. To further enrich your journey in Japan, let’s begin with a fundamental understanding of Kyoto.

The name “Kyoto” has become globally recognized, but what exactly is Kyoto? In reality, there exists a small district known as “the true Kyoto.” Outside of this area, the broader region belongs to Kyoto Prefecture or Kyoto City, but in a strict sense, it is not truly Kyoto. This is the first crucial point to understand.

Historically, the term “Kyoto (京都)” originally referred to a specific space where the Imperial Court, led by the emperor, governed. The origins of present-day Kyoto trace back to the establishment of Heian-kyo in 794, but before that, places such as Nara, Osaka, and southern Kyoto were also considered “Kyoto” at different times. Over time, however, “Kyoto” became a proper noun referring exclusively to the current city.

By understanding this fundamental point, one can see Kyoto’s essence for the first time. In other words, knowing this background enriches and deepens the experience of Kyoto tourism. However, such insights are rarely written in guidebooks.

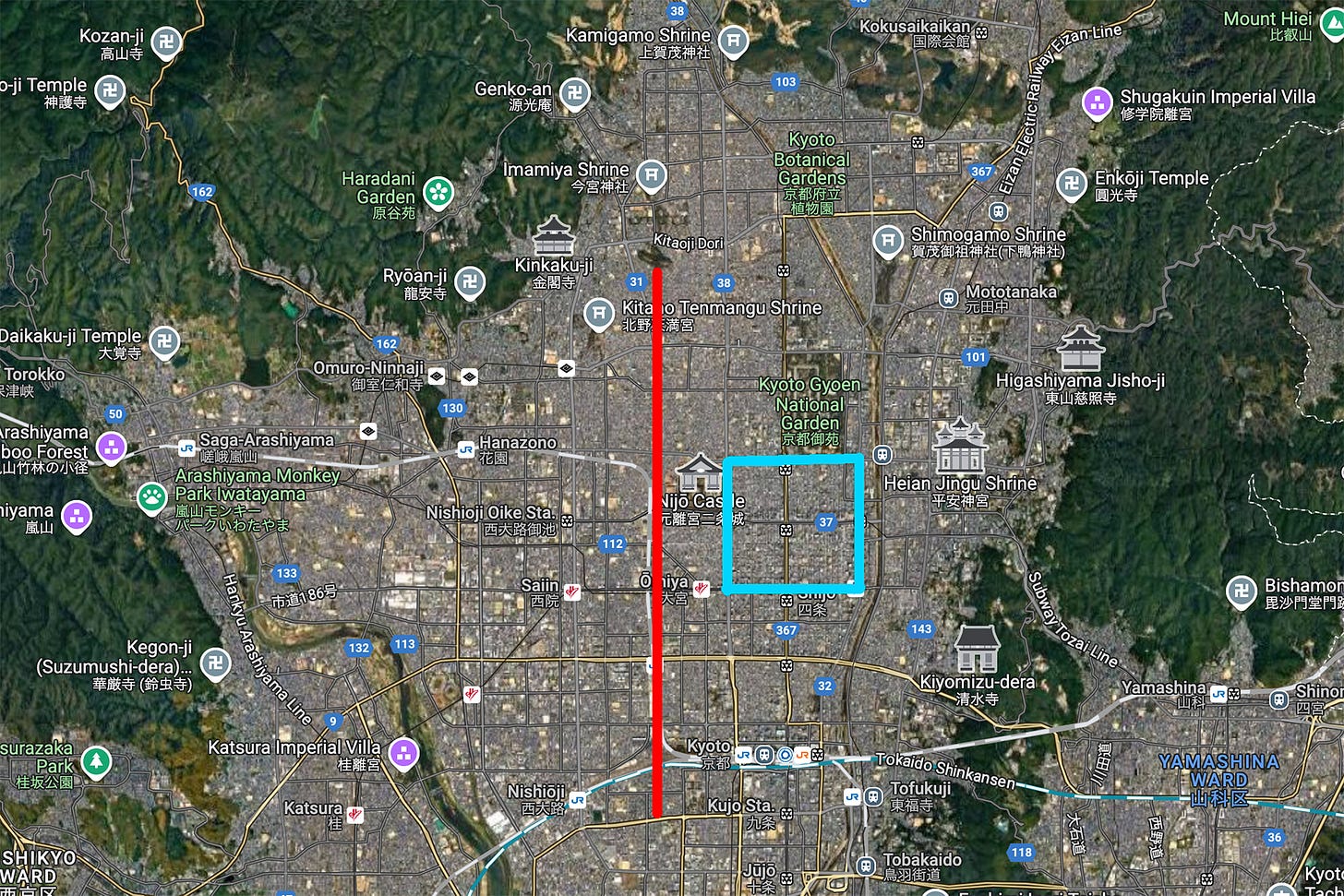

Looking at modern Kyoto, the area known as “the true Kyoto” is centered around the Kyoto Imperial Palace (Kyoto Gyoen), where emperors resided until the Edo period. It is defined by:

• Kawaramachi Street to the east.

• Horikawa Street to the west.

• Marutamachi Street to the north.

• Shijo Street to the south.

Only this inner district is considered “the true Kyoto.”

As a result, the areas that many tourists visit as part of Kyoto sightseeing are, strictly speaking, not Kyoto but “outside Kyoto.” In other words, most tourists are not actually exploring Kyoto itself—they are exploring its outskirts.

If you have visited Kyoto before, you may realize that the highlight of Kyoto tourism—visiting temples and shrines—actually takes place outside Kyoto, rather than within it.

The historical circumstances that led to this small, exclusive district becoming “the true Kyoto” remain unclear. At the very least, we know that Kyoto’s central axis did not remain fixed from the founding of Heian-kyo onward. Instead, the city’s center gradually shifted from west to east over time.

Some readers may be familiar with Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s classic novel Rashomon (1915) or Akira Kurosawa’s film adaptation Rashomon (1950). The “Rashomon” in these works was originally the main southern gate of Heian-kyo. However, its origins predate the Heian period, as the Rashomon concept was first established in 710 during the Nara period in Heijo-kyo.

Historically, this southern gate district (Rajo-mon (Rashomon) area) fell into disrepair relatively quickly after the establishment of Heian-kyo. By the late 10th century, it had become a wasteland, and people gradually moved eastward to what is now the central area of Kyoto.

There are various theories regarding why this happened, but historical records suggest that Rajo-mon was destroyed by typhoons in 816 and again in 980, after which it was never rebuilt.

Rajo-mon was reportedly located southwest of present-day Kyoto Station, near the west side of To-ji Temple. Historically, To-ji had a twin temple, Sai-ji, which no longer exists. It is believed that Rajo-mon stood between these two temples, but its exact location remains unknown.

Why is Kyoto’s ancient past so difficult to define? One major reason is that Kyoto has repeatedly been a battleground throughout history. As a result, the city has undergone cycles of destruction and reconstruction, leading to constant renewal.

Each time this happened, Kyoto shed its old form and took on a new identity, making it difficult to reconstruct the exact appearance of the city during the Heian period.

One of the primary reasons behind Kyoto’s west-to-east migration was its geographical environment.

An interesting research finding was published by Harushige Kusumi, a former professor at Kansai University’s Faculty of Environmental and Urban Engineering. His research suggests that when Heian-kyo was first established, the Imperial Palace was not located on Kyoto’s eastern side (as it is today), but rather in the west, near Mount Funaoka.

At that time, a grand boulevard measuring 84 meters in width stretched from the southern Rajo-mon gate to the palace, known as Suzaku Boulevard. The palace entrance was marked by Suzaku Gate, forming the heart of Heian-kyo. Recent research has revealed that this boulevard once ran through what is now western Kyoto, but its full layout remains uncertain.

However, for some reason, the Imperial Palace was relocated to the east at an early stage. As emperors and aristocrats moved eastward, this area gradually became the center of Kyoto, shaping the city as we know it today.

What caused this dramatic shift in Kyoto’s geography and demographics? One possible explanation, proposed by Kusumi, is geological differences.