How Japan Adopted Christmas and the Forgotten Calendar Shift

From the Tenpō Calendar to a Commercial Celebration of the West

Today, I would like to explore the remarkably strange background behind how Christmas came to be celebrated in Japan.

Although Japan has historically had little connection with Christianity, every year around this time, the entire country becomes immersed in a Christmas atmosphere. It is true that this phenomenon largely stems from product marketing in an industrial society, yet at its core lies a major shift in Japan’s calendar system.

The adoption of a formal calendar in Japan can be traced back about 1,400 years, when Chinese calendrical methods were introduced by immigrants. From that point on, Japan regularly imported updated versions of the Chinese calendar, developing its concepts of time—and eventually its own history—in the process. This continued for quite a long time, but during the Edo period (1603–1868), there was a backlash against Chinese dependence, and momentum grew for creating a domestically produced calendar.

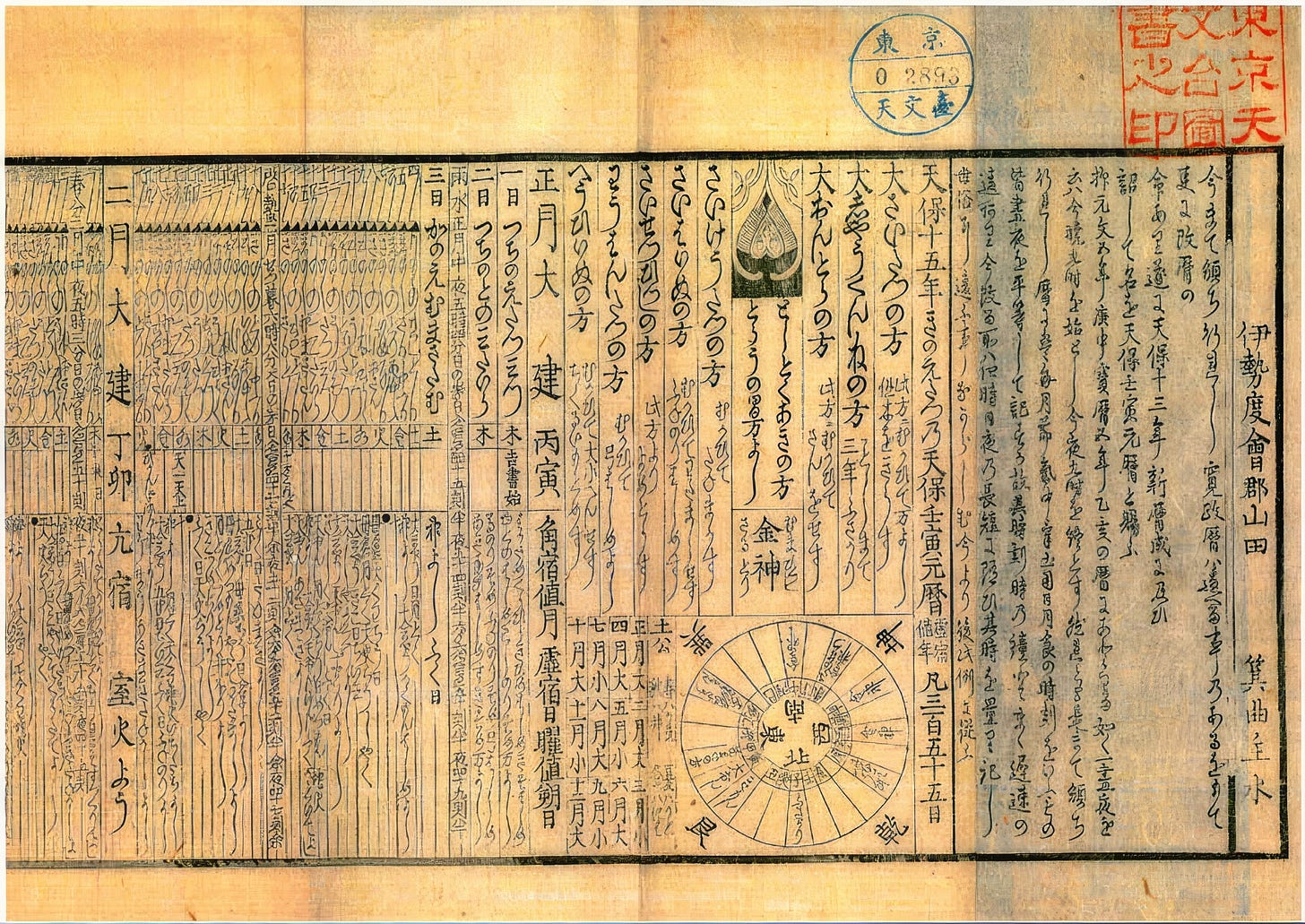

That trend culminated in the development of Japan’s first homegrown calendar, known as the Jōkyō Calendar (1685–1755). In China, which had a history marked by wars and upheavals, the calendar was seen as vital to maintaining the ruling dynasty’s authority, as it helped predict potential disasters. Driven by a similar sense of urgency, Japan refined its own calendar, eventually reaching peak accuracy with the Tenpō Calendar (1844–1872). It’s an example of how something initially borrowed from abroad could, in time, surpass the original—a story some say is characteristically Japanese.

The shogunate demanded a highly precise calendar in order to foresee and avoid disasters that might destabilize its regime. In reality, many people in various regions were already suffering due to famine and natural calamities. Not only was Japan closed off to the outside world (the policy of sakoku), it also had numerous internal borders, and crossing these without permission was punishable by death.

Still, those who had lost their homes had to risk crossing borders if they hoped to survive, which could lead to large-scale migration—and potentially even the overthrow of the government. Ironically, that same need to maintain power spurred the development of an extremely sophisticated calendar.

Yet no sooner had the Tenpō Calendar come into use than, in 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry’s U.S. Navy fleet arrived in Japan. Taking advantage of the ensuing turmoil, Scottish arms merchants—part of the British Empire’s strategy to open new markets—fomented a military coup that toppled the shogunate, which had ruled for 265 years, with astonishing ease.

Thereafter, the new government hurriedly adopted cutting-edge Western systems across the board, yet it continued using the Edo-period calendar rather than the Western Gregorian calendar. The reason was that the lunar-solar Tenpō Calendar was actually more accurate than the Gregorian. If it was more accurate, why was it ultimately replaced?

The answer lies in financial hardships. Under the existing lunar-solar system, 1873 would have had a leap month, meaning the government would need to pay civil servants for thirteen months’ worth of wages. Furthermore, December 1872 would have lasted only two days, but still required a full month’s pay. This was a critical issue for a government already strapped for cash. In response, they claimed “Westernization” in the name of modernity and forcibly changed the calendar system.

By discarding its painstakingly developed domestic calendar, Japan adopted the Gregorian system of twelve set months without leap months. Put bluntly, the Meiji government’s financial challenges drove the Westernization of the nation’s calendar. Within this context, and as industrial society began reaching every corner of the country, the 20th century saw the arrival of something Japan had never experienced before: the celebration of Christmas. Businesses immediately seized on this as a money-making opportunity.

Then, by chance, Emperor Taishō (r. 1912–1926) passed away on December 25, 1926, making that date feel more meaningful for the Japanese. Personally, I think December 25th was so strongly tied to the emperor’s passing—at least up until the postwar period—that people tended to think of it as a day of remembrance. As a result, Christmas Eve ended up becoming the livelier occasion we know today.

During Japan’s period of rapid economic growth, only having a single “special day” wasn’t very profitable, so retailers pushed both Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, effectively doubling the holiday’s economic impact. In other words, while Christmas in the West originally grew out of a desire to spread Christianity, in Japan, it arose for purely economic reasons. This has produced two rather curious days, fundamentally unrelated to religion, but propelled by financial motives.

These days, if you walk the streets of Japan at Christmastime, you’ll see countless young couples strolling arm-in-arm, and virtually every shop remains open and bustling. For visitors from Christian-majority countries, this may appear as a strangely enchanting spectacle from another world.

In this way, the Japanese have shown extraordinary flexibility in absorbing foreign cultures and rebuilding them in distinctive ways. Whether you view that as adaptability or mere superficiality is up to you. As I watch the city’s Christmas bustle, I can’t help but be reminded of how uniquely enigmatic the Japanese people can be.