How to Choose a Shrine in Japan The Overlooked Depth of Worship

Why Visiting the Wrong Shrine Can Have Unintended Consequences

In this article, I will discuss how to properly choose a shrine for worship—a perspective that may differ greatly from how many tourists casually visit shrines in Japan.

First and foremost, there are no fixed rules for shrine visits. The manuals commonly circulated today are, in essence, political constructs established in the modern era. That is precisely why it is so important to cultivate your own deep understanding of shrines and the history of Shinto.

When visiting Japan as a tourist, shrines are promoted as “tourist spots,” so it’s almost inevitable to arrive with little knowledge of their background. However, in reality, there are numerous lineages of shrines, and they can be broadly divided into those that suit you and those that do not. This distinction is fundamental.

Even when I speak with my Japanese friends, the vast majority of them visit shrines for sightseeing purposes. Very few people understand the historical background of a given shrine or which Kami are enshrined there. This is truly a sad state of affairs.

Given that even the Japanese are in this situation, it’s hardly possible for foreign tourists to grasp the unspoken manner in which shrines should be visited. The reason is simple: no such guideline exists (and it cannot be created).

Nevertheless, Japan is often regarded as a mysterious, spiritual country and people. Without understanding this viewpoint and approaching shrines accordingly, even a lovely trip to Japan may end up in disappointment.

By way of example, there are only a small number of Japanese who recognize that one should visit a shrine exclusively in the early morning if one truly understands the significance of shrine worship. Some visit a particular shrine daily, while others limit their visits to specific times of the year. It is not something you do arbitrarily at your own convenience.

Contrary to what many believe, visiting a shrine in the afternoon is said—since ancient times—to be spiritually hazardous. Those who truly understand do not set foot in a shrine (or a temple, for that matter) after midday.

At the same time, even if you make an early-morning visit, if the shrine is not suited to you personally, it will not bring any positive effects. One key indicator for this is the lineage of the Kami. Understanding this point is nearly impossible not only for foreign visitors, but for many Japanese people as well.

Spurred by the Great East Japan Earthquake, the 2010s in Japan saw a “power spot” boom—heavily promoted by the media—in which large crowds began seeking out shrines believed to possess special spiritual energy.

However, this led to a surge in people suffering from poor health or experiencing setbacks in their lives afterward. The reason is that they visited shrines that were not compatible with them, simply following media hype. In other words, Kami issued a warning to people who seek answers to life’s questions solely from external sources.

I will write more about this on another occasion, but a typical example is Kyoto, famous worldwide as a tourist destination. You may be surprised to learn that the areas in Kyoto lined with shrines and temples—often regarded as prime tourist spots—were originally places where the living were not meant to set foot. Unless there is a special reason, I personally never enter these areas.

Of course, most tourists are unaware of this history. As a result, they plan fun trips to Kyoto, visit various shrines and temples purely on the basis of their travel itineraries, and end up feeling unwell—sometimes spoiling their entire trip. This happens quite frequently. It is especially risky for people with a strong spiritual sensitivity. My sincere hope is that those who make the long journey to Japan will not return home carrying misfortune.

As you can see, the essence of a truly profound journey through Japan does not lie in the visible world; rather, it involves venturing into the invisible. Therefore, deep historical knowledge and cultural refinement—above all, self-reflection based on reason—are indispensable.

Some may find it a bit harsh, but I advise foreign visitors to avoid entering shrine grounds when they come to Japan. Even without stepping inside, offering a bow at the torii (the gate at a shrine’s entrance) is more than enough. Beyond that point is the protective boundary of the Kami, and there is no need to enter.

There are, however, a few exceptions. Certain shrines enshrine deities originating from outside Japan. Most of these trace back to specific regions in China or Korea. Those with ancestral roots from these regions can visit such shrines without issue. But again, without a deep understanding of Japanese history, it’s difficult to make these distinctions.

Among my Japanese friends, several have told me they can no longer casually visit shrines after hearing my explanations.

Yet this compels us to reflect deeply on how, since the modern era, shrine visits have been conducted out of human, self-centered motives. One might even consider this perspective a sort of “anti-modern” stance, aimed at restoring the original spirit of shrine worship.

Why? Because when most Japanese people visit a shrine, they tend to pray for blessings in their own lives or for their families, without much regard for the Kami actually enshrined there. A shrine is not a place to dump your secret wishes onto the divine. Though such awareness was once commonplace in Japan, the situation today has deteriorated significantly.

Dismissing the “invisible world” as mere superstition and ignoring it at our own convenience has led us to a conspicuous state of confusion.

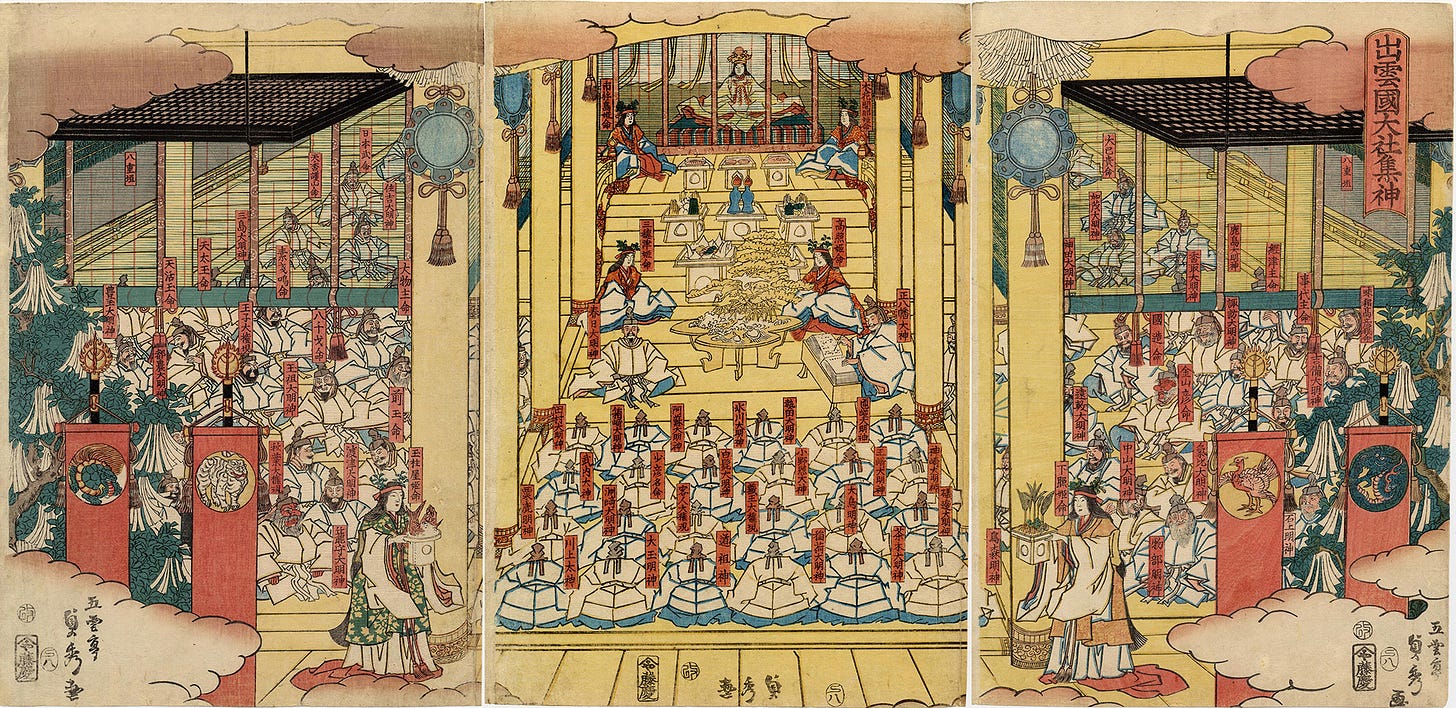

In the Kojiki (compiled in 712) and the Nihon Shoki (compiled in 720)—Japan’s oldest extant mythological records—over three hundred Kami appear. Each of these Kami belongs to a specific lineage, and these lineages are closely tied to particular places and the people who have historically enshrined them. This exclusivity must not be ignored.

That said, truly understanding the lineages of over three hundred deities requires deep familiarity with mythic tradition. It is extremely difficult for modern-day Japanese individuals to know which lineage they themselves belong to. Therefore, in the Kojiki, there is one crucial distinction introduced: between the “Amatsu-Kami (天つ神)” and the “Kunitsu-Kami (国つ神)”.

I will delve deeper into this subject another time, but for now, I hope this article provides some insight into how profoundly different the reality of shrine worship can be from what is commonly portrayed.