Unraveling the Mysteries of Kūkai and the Birth of Shingon Buddhism

Kūkai’s Lost Seven Years and the Path to Shingon Buddhism

In this article, we explore the mysteries surrounding Kūkai, the pioneering monk who founded Shingon Esoteric Buddhism and advocated the doctrine of Sokushin Jōbutsu (即身成仏, attaining Buddhahood in this lifetime).

It was Kūkai (774–835) who laid the foundation for the flourishing of Esoteric Buddhism in Japan. Also known as Kōbō Daishi, he traveled to Tang China, which at the time was a hub of advanced culture. There, he studied at Qinglong Temple in Chang’an and encountered Huiguo (恵果和尚), a legendary Buddhist master. Under Huiguo’s tutelage, Kūkai absorbed the entirety of the Esoteric Buddhist teachings that had been transmitted to China.

Upon returning to Japan, Kūkai established a new Buddhist school known as Shingon Esoteric Buddhism (Shingon-shū). He achieved many great feats, and numerous legends have been passed down about his life. His journey to China as a long-term study monk began in 804, when he was 31 years old.

Surprisingly, until that point, Kūkai was virtually unknown. People at the time questioned how an obscure monk in his thirties—not particularly young—was selected for the Kentōshi (遣唐使), the official Japanese mission to Tang China, which was a major state project.

Moreover, Kūkai returned to Japan in 806, having completed his studies in just two years, despite the original plan being a 20-year stay. He met his master, Huiguo, in May 805, but by December of that same year, Huiguo had passed away. This meant that Kūkai received the entirety of the Esoteric Buddhist teachings in only six months. It is said that Huiguo recognized Kūkai’s talent the moment they met and, bypassing his thousand other disciples, entrusted him with the entirety of his teachings.

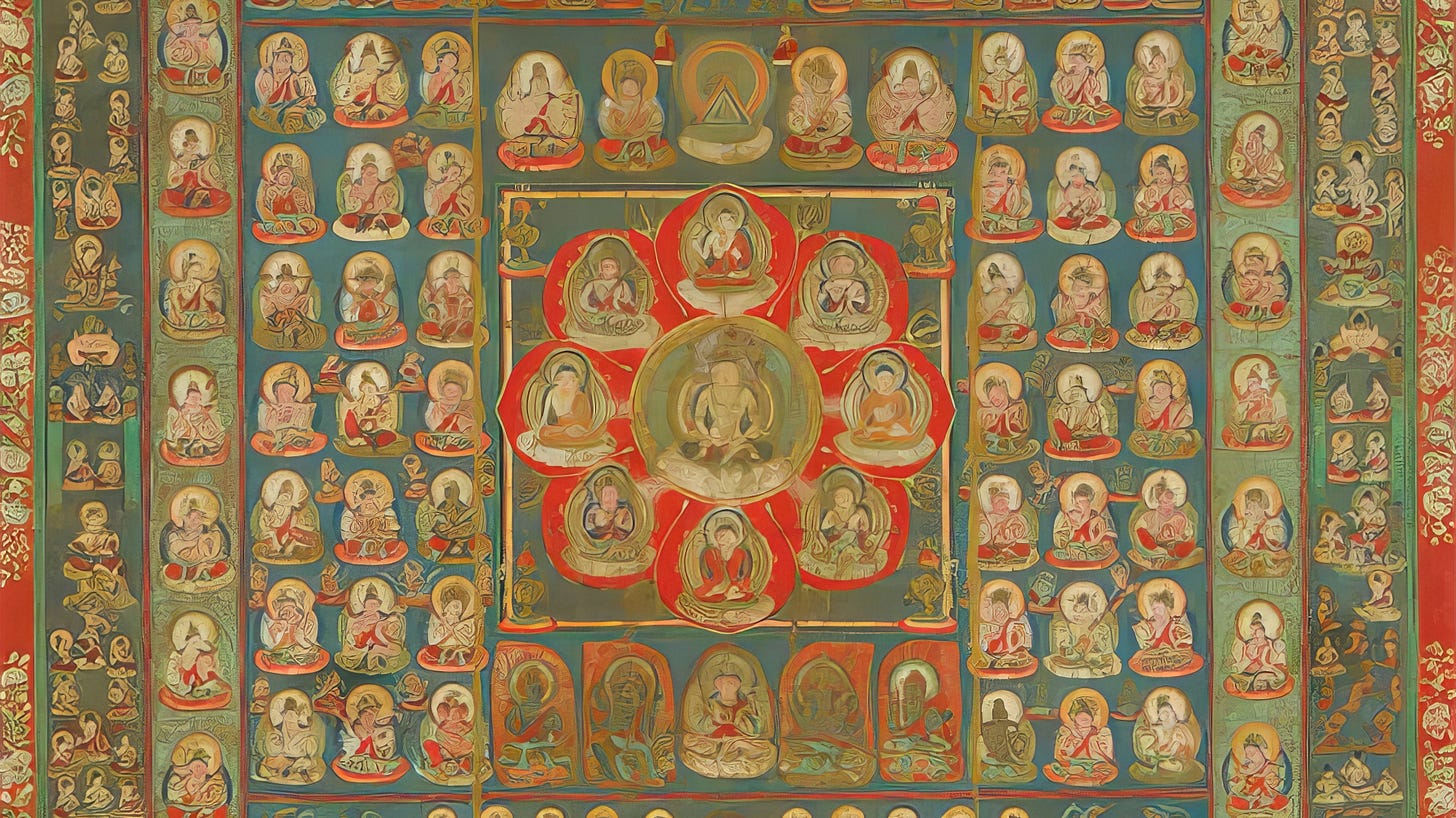

In addition to his spiritual training, Kūkai dedicated himself to creating mandalas, ritual implements, and transcribing numerous Buddhist scriptures, spending all his funds for the sake of Japan’s future. The texts he brought back to Japan numbered 216 sets, totaling 461 volumes, all of which were previously unknown in Japan.

Notably, there was no overlap between these scriptures and the Buddhist texts that had already been introduced to Japan. This suggests that Kūkai had already mastered all the Buddhist scriptures available in Japan before his journey.

One of the greatest mysteries surrounding Kūkai is how he was able to amass such substantial financial resources despite being virtually unknown in the Buddhist community and not from a wealthy family. This remains unexplained to this day.

Additionally, before his journey to China, how did Kūkai acquire such a high level of fluency in Chinese that he required no interpreter? This too remains a mystery.

Another enigma is the period known as Kūkai’s “Seven Lost Years”—the time between 797 and 804, before he traveled to China.

This was a period of great political upheaval in Japan. In 794, the capital was moved from Nara to Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto). The emperor at the time, Emperor Kanmu (r. 781–806), ordered this relocation. However, behind this decision was a deep fear of vengeful spirits, resulting from brutal political struggles within the imperial family.

The relocation of the capital was not merely a political move; it was also a way to escape the violent cycle of assassinations and betrayals that had given rise to restless spirits seeking vengeance. The imperial court invested heavily in exorcisms and protective rituals, enlisting the help of Shintō priests and Buddhist monks to counteract these spirits. Despite their efforts, however, the results were less than satisfactory. The court then began searching for someone capable of constructing a spiritual barrier (“kekkai, 結界”) around Heian-kyō to ward off vengeful spirits.

It was during this time that the 23-year-old Kūkai is said to have received a divine revelation and discovered the Dainichi-kyō (大日経, Mahāvairocana Sūtra), a scripture rooted in Indian Esoteric Buddhism. Through this discovery, he encountered the concept of Sokushin Jōbutsu (attaining Buddhahood in this lifetime), studied its teachings independently, and achieved profound enlightenment. Then, he suddenly vanished from historical records.

Some theories suggest that during these seven lost years, Kūkai was secretly employed by the imperial court to construct the spiritual barrier (kekkai) around Heian-kyō. It is speculated that his success in this clandestine mission earned him massive financial backing and political support, which enabled him to be exceptionally selected as a member of the Kentōshi mission to Tang China.

There is strong circumstantial evidence supporting this theory. Kūkai’s own autobiographical writings omit any mention of these seven years, and no official imperial records from that period mention him either. This suggests that he may have been involved in a highly classified imperial project.

Additionally, during this time, Kūkai gained the trust of the court and established connections with Tang Buddhist monks and scholars who were staying in Japan. This may explain how he acquired his extraordinary fluency in Chinese before ever setting foot in China.

Thus, after his mysterious seven-year absence, Kūkai reappeared—suddenly possessing immense financial resources and exceptional language skills—and embarked on his journey to Tang China. In just two years, he fully mastered the profound teachings of Esoteric Buddhism. Upon his return to Japan, he quickly became involved in major state projects and established Shingon Buddhism as a new religious tradition.