Ending Hereditary Priesthood and the Rise of State Shinto in Meiji Japan

Meiji-Era Reforms and the Restructuring of Shinto as a State Institution

In the previous article, we discussed how, with the beginning of modern Japan, the Meiji government rejected the old Shinto systems that had existed from ancient through medieval times. They introduced a variety of new institutions in pursuit of establishing a Western-style modern state.

Among these measures, the most shocking was the abolition of the hereditary system for Shinto priests. In this article, we will explore how Shinto attained overwhelming dominance in the early Meiji period against this backdrop.

Originally, the system of hereditary priesthood was carried out at prominent shrines across various regions. A local clan, firmly rooted in that land, would hold the position of priesthood for generations. The question of how a specific clan came to preside over a particular shrine can also be traced back to descriptions in ancient texts such as the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki. In another sense, the history of shrines—as we now understand them—could be seen as the story of how certain clans were officially recognized and incorporated into a larger framework.

For instance, Izumo Taisha in Shimane Prefecture is one of the few shrines that continues its hereditary priesthood to this day, currently under its 84th high priest. That role is still carried out by the Senge family (千家家), which is one of two historically branched lineages (the other being the Kitajima family, 北島家).

Another crucial reference point here is Kono Shrine (籠神社) in northern Kyoto Prefecture. Kono Shrine also avoided the effects of the Meiji-era abolition of hereditary priesthood, and even now, the priestly role is held by the Amabe clan (海部氏). The current high priest there is the 82nd in an unbroken line.

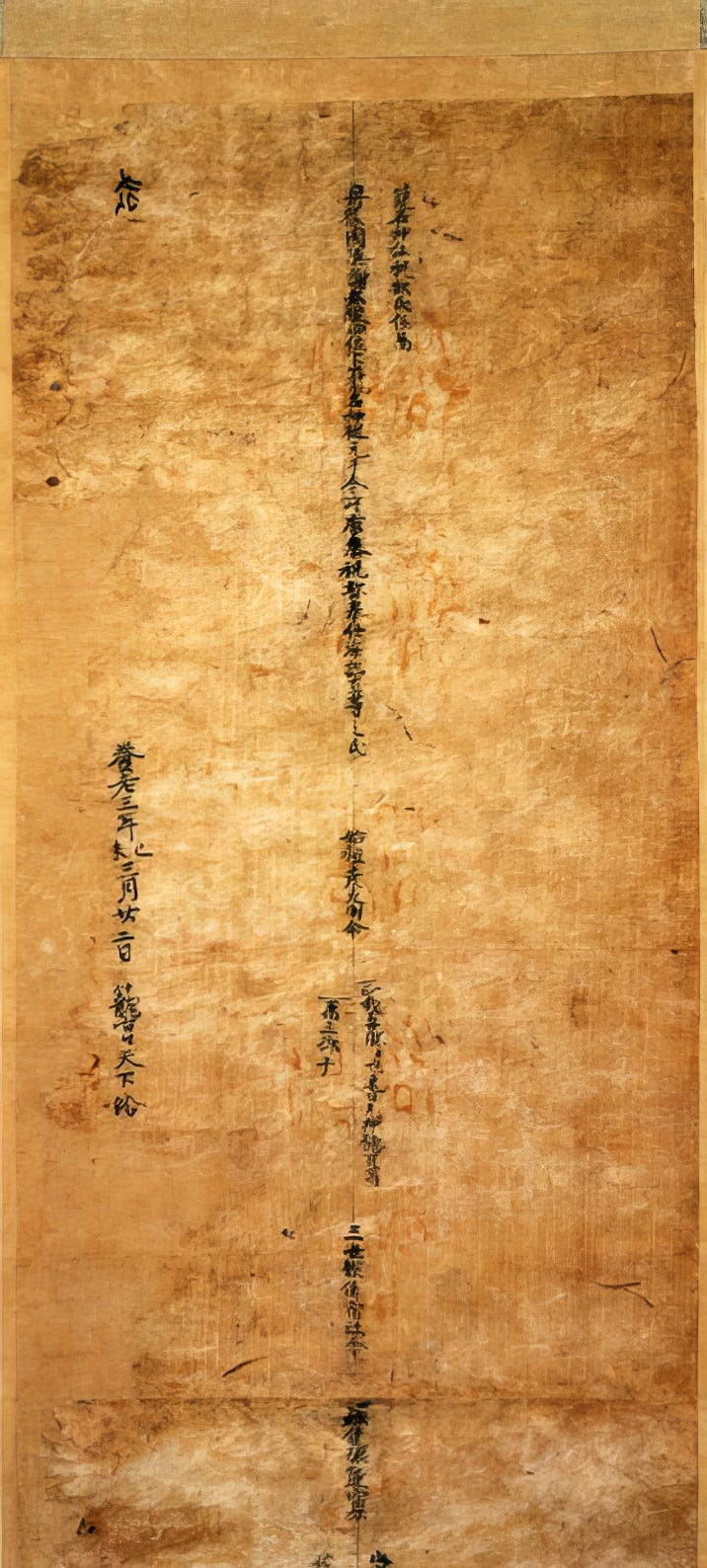

Kono Shrine is uniquely important in Shinto history because it holds the oldest surviving genealogy in Japan—known as the Genealogy of the Amabe Clan (海部氏系図). Copied in the Heian period, this document is now designated a National Treasure.

Readers may wonder why the most famous shrine in Japan, Ise Jingū in Mie Prefecture, does not fit this pattern. In truth, Ise Jingū has already abolished hereditary priesthood, and in the early modern era, there were times when its high priest was neither local nor connected to Shinto at all.

Likewise, in the famous sightseeing area of Arashiyama in Kyoto, the highest-ranking shrine is Matsuo Taisha (松尾大社), which also lost its hereditary priesthood during the Meiji reforms. As a result, people with no ancestral ties to the shrine serve as its priests today. Historically, the role of high priest there had been passed down within the Hata clan (秦氏). Before modern times, there were countless shrines around the country with similar practices.

The Meiji government first intervened at Ise Jingū. Their aim was to dismantle the traditional characteristics of shrines in order to reshape them into institutions that would align with the formation of a modern nation-state.

In doing so, shrines—traditionally dedicated to regional deities who protected local people—were gradually redefined as institutions devoted to the single, unified state. Seated at the pinnacle of this newly centralized system was Ise Jingū, in other words, a highly political shrine chosen through bureaucratic processes.

This is why Ise Jingū’s present status as the “most prestigious shrine in Japan” only dates back to the modern era; it held no such position before that time.

So what political forces lay behind this decision? Surprisingly, the individuals who had the greatest influence were not powerful Shinto leaders from before the modern era, but a certain group within Buddhism.

Although one might imagine that Buddhism held absolute sway throughout Japanese history, that dominance was limited to certain eras. In fact, over the course of the Edo period (which lasted 265 years), the influence of Buddhism weakened considerably.

The Edo period saw the great flourishing of Confucianism. In reaction, a group of scholars emerged to champion Japan’s indigenous traditions, referred to as “Kokugaku” (National Learning). This movement gained momentum in the latter half of the 18th century and continued to grow in strength until the end of the Edo period, a development that is deeply interwoven with the events leading to the Meiji Restoration.

Indeed, the Meiji Restoration began with the “the Declaration of Imperial Rule” (王政復古の大号令), a proclamation aimed at dismantling the Tokugawa shogunate’s power by demanding the resignation of the Tokugawa clan, thus restoring governance under the emperor. A key point in this decree is that, for the first time in Japanese history, the notion of Shinto’s absolute supremacy was explicitly tied to the emperor’s authority.

The mastermind behind this was Iwakura Tomomi (岩倉具視, 1825-1883), born into a family closely connected to the imperial court in Kyoto. The two major forces driving the Meiji Restoration were the Chōshū domain (in present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture) and the Satsuma domain (in present-day Kagoshima Prefecture), and Iwakura held a pivotal position mediating among these and other domains.

Why did Iwakura place Shinto at the foundation of the new modern state? At the time, he was greatly influenced by a Kokugaku scholar named Tamamatsu Misao (玉松操, 1810–1872), whose central idea was “Return to Jinmu,” referencing Japan’s mythical first emperor. This ideal of restoration, “Return to Jinmu,” became the bedrock of the movement.

With Iwakura’s political skill, once the new government was established, it quickly moved away from the Confucian influence inherited from the Edo period. To establish Shinto’s supremacy, the state began to suppress Buddhism at a national level. Initially, these measures were enacted without any discussion or compromise with Buddhist leaders, provoking an immediate and intense backlash.

Thus, as Japan entered modernity, conflicts over dominance erupted in all directions, entangled in the complex interplay of Shinto, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Western ideas.