Japanese Ink Painting’s Origins and Its Transformation from China

From Calligraphy to Fine Art The Evolution of Japanese Ink Painting

When discussing Japanese art that attracts considerable interest from travelers, one example that comes to mind is Japanese ink painting (sumi-e). However, it is not widely known that the history of ink painting in Japan began under rather mysterious circumstances. In the following segments, I will outline the background of this art form in several parts.

Needless to say, the roots of Japanese ink painting lie in Chinese art. However, ink painting did not suddenly appear in China out of nowhere; it was based on the historical and technical practice of calligraphy. Calligraphy had long been developed for practical purposes, but it began to be applied as an art form starting in the mid-period of the Later Han dynasty (25–220).

Building upon the foundation of calligraphy as an art, the intellectuals of the time then turned their attention to painting, which had previously been held in low regard. Thus began a new era in which cultured individuals practiced both calligraphy and painting, leading to the development of distinct painting techniques.

One such new form that emerged was known as hakubyō-ga (a technique that uses only outlines without color or shading, also sometimes referred to as white-line drawing).

After the collapse of the Han dynasty, during the Jin dynasty (265–420) and subsequently during the Song dynasty (420–479), numerous white-line drawings were produced. Eventually, they took shape during the Tang dynasty (618–907), a period of flourishing civilization. It was this Tang dynasty that exerted tremendous influence on Japan at the time.

In the capital of Chang’an, Chinese culture of the north and south was converging, while at the same time there was an influx of cultural influences from India and Persia. This multicultural milieu was incredibly complex and diverse, and it absorbed these various elements, fueling further cultural development.

Within this process, a reactive revival of Han Chinese cultural identity took place. An intriguing phenomenon followed: heightened attention to “line,” which had been cultivated through historical calligraphy, and a backlash against the excessive “color” of foreign cultures. Accordingly, some intellectuals, seeking to unify calligraphy and painting according to existing traditions, rejected color and elevated white-line drawing—devoid of color—to the highest artistic level.

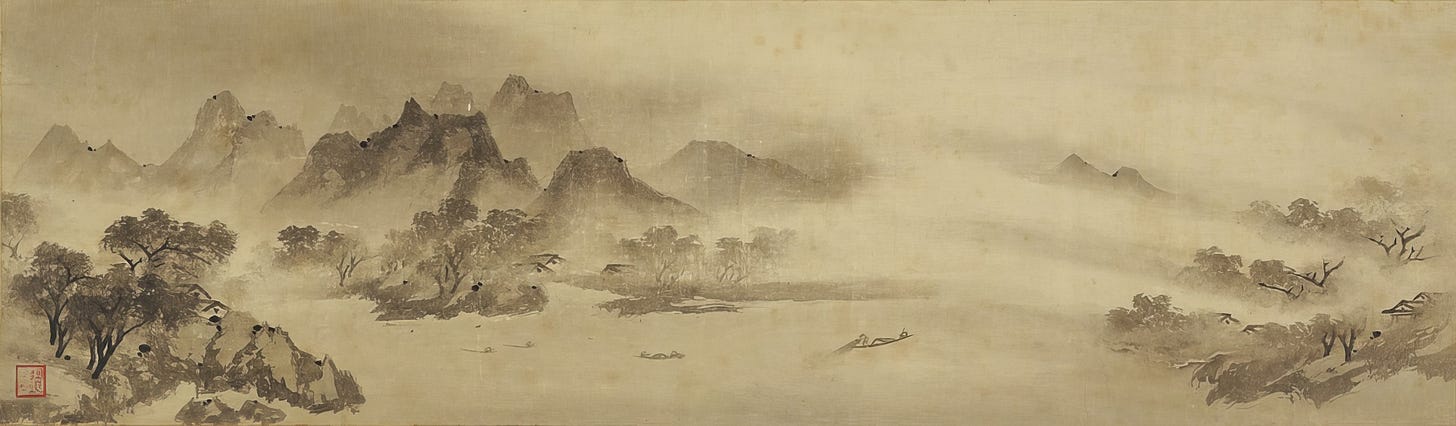

At around the same time, the An Lushan Rebellion (755–757) broke out, generating an energy that opposed aristocratic rule and gave rise to ink painting, which was not aristocratic white-line drawing. Put simply, white-line drawing is characterized by a focus on “line,” while ink painting is distinguished by a focus on “surface.” Yet, in line with the trend of rejecting foreign culture, ink painting also gradually moved toward monochrome, aiming to depict images solely in ink.

Looking at this from the relationship between “brush” and “line,” and “ink” and “surface (color),” it becomes somewhat clearer.

Nonetheless, discussions of painting in China as they relate to the “brush” and “ink” generally prioritize the brush. For example, in Notes on Brushwork (Bǐfǎ Jì), written by Jing Hao (ca. 850–ca. 911) during the Tang dynasty, it is stated that “the brush depicts the volume and vitality of forms,” while “ink conveys the yin-yang interplay and the three-dimensionality of concavities and convexities.”

This Chinese cultural perspective, which places the “brush” at the core (acting like a subject), contrasted with Japan’s preference for a culture that places greater emphasis on “ink” (acting more like a predicate). This difference became an important factor influencing the development of Japanese ink painting, and behind it lay the influence of Zen in later periods.

Particularly important in ink painting was the technique known as haboku (破墨 / “broken ink” technique). By inverting the conventional understanding of traditional brush-centric techniques—where the brush outlines forms and the ink fills them in—Japan succeeded in achieving a more predicate-oriented means of expression.

Moreover, a brush-free technique known as hatsuboku (溌墨 / “splashed ink” technique) was developed in China. This created the possibility of mitigating the emphasis on brush-drawn outlines, although this was essentially an attempt—within the Chinese “subject-oriented” perspective—to discover a “predicate-oriented” viewpoint, pursued in a somewhat retrospective or compensatory manner. It was the Japanese ink painters who refined this approach into a purer form.

Thus, the key lies not merely in differences of technique but in discerning the differences in linguistic structures.

Even so, hatsuboku still relied on a dualistic mindset of “brush as primary, ink as secondary” (筆主墨従) and “ink as primary, brush as secondary” (墨主筆従). Hence, at that stage, there was no opening for Japan to fully embrace ink painting.

During that period, the treatise Preface on Painting Landscapes (Huà Shānshuǐ Xù) by Zong Bing (375–443) once again came into focus. As the earliest theoretical work to apply landscape thought to painting, it profoundly influenced the rise of landscape ink painting in China. Broadly speaking, this style formed in the mid-10th century, around the time the Northern Song dynasty was established.

In this new current, there was a strong push toward the integration of the internal and external, and a merging of the subjective and objective. Landscape painting developed on this foundation, but once again, it did not align with the core of Japanese cultural sensibilities.

Moreover, at that time, very few Chinese landscape paintings made their way into Japan, and even the small number that did were accessible only to certain aristocrats. This trend continued in Japan until around the 14th century.

Despite the fact that ink painting underwent a unique evolution in China, as stated earlier, it did not exert a strong influence on Japan for a long time. Yet, by a stroke of good fortune, some strands of ink painting—deemed to have no value and rejected by China’s aristocratic society—found their way to Japan.

The individual who produced these works was Muqi (Mokkei; 1210?–1270?), a Zen monk active in the late 13th century.

Continued in Part 2.