Rai San’yō and the Unofficial History That Shaped Japan

Rai San’yō’s Nihon Gaishi and Its Role in Undermining Tokugawa Rule

In this article, we delve into the life and legacy of Rai San’yō (頼山陽, 1780–1832), a historian who, for the first time, challenged the constraints of government-controlled historiography and had a profound influence throughout the late Edo period.

Born into a family of maritime traders in the Hiroshima Domain, San’yō’s upbringing was shaped by his father, an intellectual who studied in Osaka and later opened a private Confucian academy. In 1781, San’yō’s father was appointed as a retainer responsible for Confucian education in the Hiroshima Domain, prompting the family to move to Hiroshima.

Under his father’s guidance, San’yō showed remarkable intellectual promise from a young age. His talent caught the attention of Shibano Ritsuzan (1736–1807), one of the foremost Confucian scholars of the time and an advisor to the shogunate. To meet Ritsuzan’s expectations, San’yō began writing Tsūkan Kōmoku (通鑑綱目), a commentary on historical records that garnered significant recognition.

The Edo period was heavily influenced by Confucian philosophy, particularly Zhu Xi’s Neo-Confucianism, which the Tokugawa shogunate had adopted as a cornerstone of its feudal system. This rigid intellectual framework left little room for alternative schools of thought, and dissent was not tolerated. Like his father, San’yō was initially steeped in Zhu Xi’s teachings, and his early work, Tsūkan Kōmoku, reflected this tradition, focusing on the Confucian principle of “righteousness and legitimacy.”

By the age of 18, San’yō had already set his sights on dedicating his life to the study and writing of history. However, his brief time studying in Edo convinced him that his aspirations could not be fulfilled within the confines of the domain system. Returning home the following year, he concluded that breaking free from his domain’s restrictions was essential to achieving his scholarly goals.

In the feudal society of the time, children of retainers were bound by strict codes of loyalty, and leaving the domain without permission—referred to as dappan (脱藩, defection)—was considered a grave crime. Nevertheless, at the age of 21, San’yō attempted to escape to Kyoto and Osaka.

When his attempt failed, he was forcibly returned to Hiroshima and confined to a zashiki-rou (座敷牢, a type of room resembling solitary confinement and considered a precursor to modern psychiatric wards), where he was labeled mentally unstable and prohibited from leaving the domain. The following year, he was placed under house arrest—a situation that lasted an extraordinary nine years.

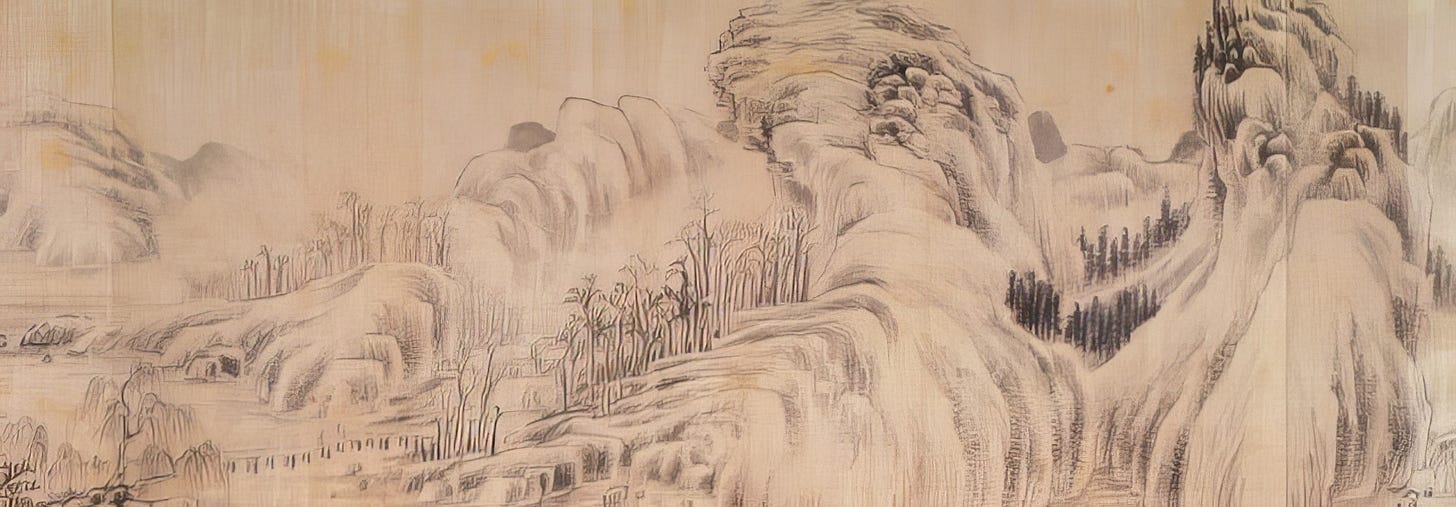

During this period of confinement, San’yō’s resolve never wavered. He devoted himself to his ideals and began drafting the manuscript for what would later become his magnum opus, Nihon Gaishi (日本外史, An Unofficial History of Japan). His persistence eventually earned him the support of those around him, and at the age of 32, he was finally allowed to travel to Kyoto. There, he continued refining his work and engaged with intellectual circles, though his reputation as a defector initially made it difficult to gain acceptance.

Nihon Gaishi would not be completed and published until San’yō was 48 years old, nearly 20 years after he began its first draft. The title itself reflected his critical stance: it was intended as an “external” history, a counterpoint to the government-sanctioned histories of the time.

Unlike the dry and bureaucratic records produced under official auspices, San’yō’s work was imbued with a personal passion for history and aimed to resonate with a broader audience. This new approach inspired a shift in historical consciousness among the public, playing a pivotal role in the intellectual underpinnings of the anti-shogunate movement during the Bakumatsu period.

**“Bakumatsu” refers to the final years of Japan’s Edo period (1853–1868), marked by the decline of the Tokugawa shogunate, the opening of Japan to the West, and the political, social, and cultural shifts leading to the Meiji Restoration.

What made Nihon Gaishi so influential? Curiously, much of its historical content was derived from earlier sources, such as the Dai Nihonshi (Great History of Japan), a monumental work initiated by Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628–1701) of the Mito Domain. San’yō also drew inspiration from medieval historians like Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293–1354) and benefited from a burgeoning interest in historical studies during his era.

Despite these influences, Nihon Gaishi was dismissed by many scholars and officials as an amateurish and unorthodox work. This skepticism stemmed from the prevailing notion that legitimate history had to align with the ruling class’s interests, and San’yō’s independent approach was seen as a challenge to this orthodoxy.

San’yō’s unique perspective lay in his reinterpretation of history through the lens of Confucian principles. While he did not openly criticize the shogunate, his narrative subtly highlighted how Japan’s political structure had deviated from its original form—direct imperial rule under the emperor.

By focusing on how the samurai class had usurped power from the imperial court, San’yō’s work implicitly questioned the legitimacy of Tokugawa rule. Ironically, he used Zhu Xi’s Neo-Confucianism, the very philosophy that underpinned the shogunate’s authority, to critique the existing order. This subversive element led to his work being regarded as dangerous.

Despite living in relative poverty, San’yō gained recognition for his artistic talents, particularly his calligraphy, painting, and Chinese poetry. These skills enabled him to form connections with influential figures, and eventually, he presented Nihon Gaishi to Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759–1829), a key Tokugawa official.

San’yō’s life was marked by struggle and perseverance. His dedication to history and his ability to channel his ideas into a form that resonated with ordinary people left a lasting impact on Japanese historical thought. Though dismissed by the elite during his lifetime, his work shaped the collective consciousness of the Bakumatsu generation and laid the intellectual groundwork for the Meiji Restoration.

Through Nihon Gaishi, Rai San’yō demonstrated that history could be more than a record of the past; it could also be a tool for reimagining the future.