Mujō and Ubasute — Japanese Reflections on Aging and Community

Aging, Death, and Communal Bonds in Folklore and Modern Japan

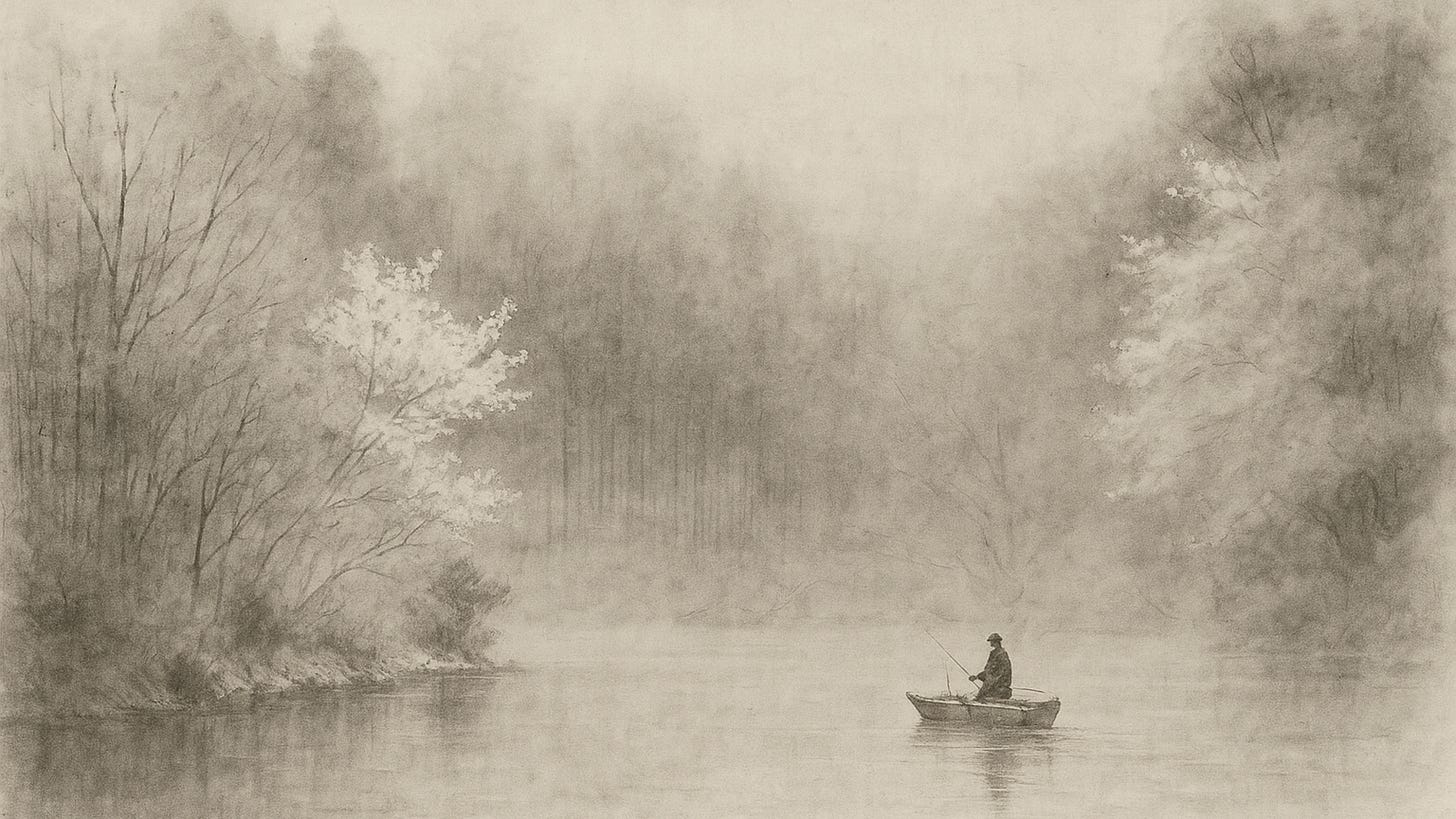

When discussing the spiritual culture of the Japanese, the concept of “mujō ” (無常, impermanence) cannot be ignored. “mujō,” derived from a Buddhist truth, refers to the ever-changing nature of everything, recognizing that nothing remains constant. Originally, it expressed a stark awareness of reality. However, Japanese people internalized this Buddhist notion of mujō not merely as a harsh termination or rupture, but as a sense of beauty and salvation. Let’s explore this concept through a contemporary perspective.

A representative example is the cherry blossoms of spring, symbolic in Japanese culture. Their beauty is found not so much in their blooming, but rather in their rapid scattering. As petals quietly flutter in the wind and fall to the ground immediately after full bloom, we feel a peculiar sense of reassurance and acceptance. This sentiment fundamentally differs from the yearning for “eternal life,” instead emphasizing a view of life and death that values the present precisely because it inevitably ends. Historically, the Japanese perspective on life and death began with contemplating death itself. Indeed, every spring, as I gaze at the falling cherry blossoms in silent reflection, I distinctly sense that ancestral sensibility alive within me.

Such sensibility is vividly evident in classical literature, indicating the long-standing cultivation of this spiritual culture. In Murasaki Shikibu’s famous work “The Tale of Genji,” the illustrious life of Hikaru Genji eventually becomes overshadowed by decline and separation. Importantly, this process of downfall is never depicted purely as a “tragedy.” This perhaps significantly contrasts with Western cultural values. Personally, I believe the concept of tragedy does not exist in Japanese culture. How, then, did the Japanese historically perceive what could conventionally be called a tragedy? It is encapsulated by “mono no aware” (もののあはれ), which can be translated as the emotional acceptance of the mujō and constant change of all things. This cultural approach does not seek “eternal happiness” but rather positively embraces the fleeting brilliance and beauty inherent in transience, making it one of our most critical sensibilities.