Keichū and Revolution of the Japanese Language

Gojūon Chart History and Cultural Transformation

In the previous article, I discussed how modern Japanese originated largely from agricultural communities in the western Liao River region of Northeast Asia, introduced by new peoples migrating to Japan during the Yayoi period. Now, we'll delve into how the foundational structure of today's Japanese language, the "Gojūon" (五十音図), was developed.

After the initial formation of Japanese during the Yayoi period, even after significant cultural impacts such as the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century, a systematic arrangement like the Gojūon chart did not appear until the Edo period. This period, named after the Edo Shogunate established by Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), came after a long era of feudal struggles. Notably, Ieyasu viewed promoting scholarship as crucial to the future of his new regime.

During this time, Confucianism, previously discussed in Shitsurae articles and originating from China, saw explosive adoption in Japan, while Buddhism, once dominant, relatively declined. In reaction, a new discipline emphasizing Japan's indigenous culture emerged: Kokugaku (国学, National Learning). Fascinatingly, the founder of Kokugaku was initially a Buddhist monk named Keichū (契沖, 1640–1701).

Keichū, active during the early Edo period, was deeply interested in Japanese classics and linguistic research despite his monastic background. Although the term "Kokugaku" didn't exist in his lifetime—it was applied retroactively—he laid its foundations. In works like "Man'yō Daishōki" (1690 / 万葉代匠記), Keichū meticulously studied the ancient Japanese poetry collection "Man'yōshū,” (万葉集) introducing a rigorous, empirical methodology for examining classical phonetics.

This shift was largely influenced by the Edo-period trend towards rational inquiry, driven by a government-promoted educational expansion accessible to commoners, breaking away from authoritative and restrictive mentor-disciple traditions. Keichū, a Shingon Buddhist priest, was proficient in Sanskrit (梵字, bonji), crucial for accurately reciting dharanis in esoteric Buddhism (密教, Mikkyō), a tradition established by Kūkai (空海, 774–835), founder of Shingon Buddhism. Keichū's deep Buddhist scholarship and passion for ancient Japanese linguistics merged uniquely, leading to the innovative organization of Japanese kana sounds into the vowel-consonant axes of the Gojūon chart.

Keichū praised Japanese phonetics as "most clear and elegant despite being from the eastern frontier, comparable to Chinese and Indian languages." Importantly, he asserted, "Our language carries spiritual efficacy," referring to the familiar concept of Kotodama (言霊). Kotodama's popularity is inherently tied to the rise of Kokugaku.

Keichū positioned Japanese linguistics on par with Chinese and Indian languages in both structure and spirituality, spearheading the effort to analyze Japan's phonetic system. This effort also served as a strong critique of contemporary intellectuals' excessive admiration of Chinese culture, neglecting Japan's heritage. His critical spirit became the cornerstone of Kokugaku's later surge, marking the onset of Japan’s gradual cultural shift away from Chinese influence.

This intellectual endeavor was challenging, given China's historically advanced civilization. Successive generations of Kokugaku scholars pursued detailed studies of "Man'yōshū," Japan’s earliest poetry anthology, dating from roughly the 7th to mid-8th centuries.

The Gojūon chart, unfamiliar to some, succinctly organizes Japanese kana phonetically into vowels (rows) and consonants (columns). For instance, the "A-row" (あ段) includes basic vowels "a, i, u, e, o,”(あ、い、う、え、お) while the "Ka-row" adds the consonant "/k/" resulting in "ka, ki, ku, ke, ko" (か、き、く、け、こ). This logical, concise arrangement systematically analyzed Japanese phonetics for the first time.

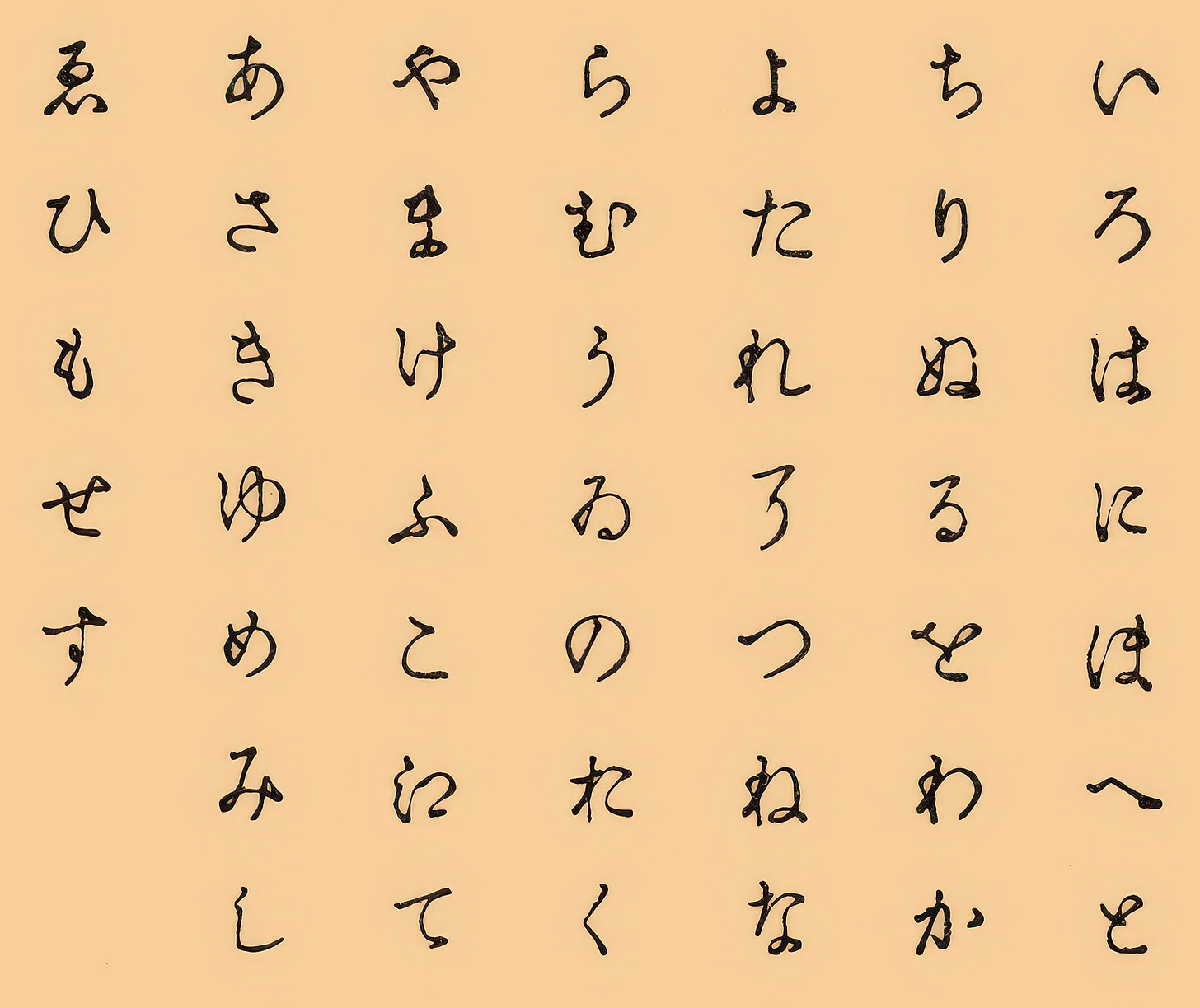

Before the Gojūon chart, scholars used the "Iroha order" (いろは順), developed between the late 10th and mid-11th centuries, comprising 47 or 48 kana characters uniquely arranged in a poem (Iroha-uta) illustrating Buddhist impermanence. Unlike Gojūon, the Iroha order lacked linguistic logic, causing significant confusion in kana arrangement throughout medieval and early Edo times. Gojūon provided flexibility, allowing rearrangements of consonant-vowel sequences without losing its structural integrity. Conversely, the Iroha order was rigidly fixed, governed by numerous secretive traditions accessible only to certain classes.

Amid the progressive atmosphere of the Edo period, Keichū standardized and named the Gojūon chart, notably in his work "Waji Shōranshō" (1695 / 和字正濫抄). This innovation made visible the intrinsic order of kana sounds, facilitating precise distinctions within Japanese phonetics and enabling a scientific approach to language study. Keichū's contributions demonstrated that Japanese had an organized phonetic structure comparable to Sanskrit and Chinese, significantly influencing future Kokugaku scholars' explorations of ancient Japanese sounds and Kotodama research.

From Keichū onward, Japanese became increasingly systematized, fundamentally transforming rural village society—previously fragmented by geographic isolation. In a broader view, the emergence of a systematic Japanese language contributed significantly to the momentum toward the shogunate's eventual overthrow in 1868.