How the Tokugawa Shogunate Used Neo-Confucianism to Rule Japan

The Rise of Hayashi Razan and the Philosophy That Shaped Edo

In this article, we will explore how the Tokugawa Shogunate, which maintained a highly structured rule for approximately 260 years, managed to govern samurai throughout Japan.

By 1600, the era of samurai-led warfare was approaching its final stage. The death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), the pioneer of national unification, triggered an internal power struggle within the government.

At this time, Japan was divided into two factions: the Eastern Army, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), and the Western Army, led by Mōri Terumoto. This conflict culminated in a large-scale battle at Sekigahara in present-day Gifu Prefecture. Ieyasu emerged victorious, seizing control of Japan and paving the way for the establishment of the Edo Shogunate.

However, even after achieving national unification, Ieyasu faced significant challenges in creating a new system of governance. The situation remained unstable, with a constant risk of uprisings against the Tokugawa rule. Thus, swift and decisive policies were implemented to consolidate power.

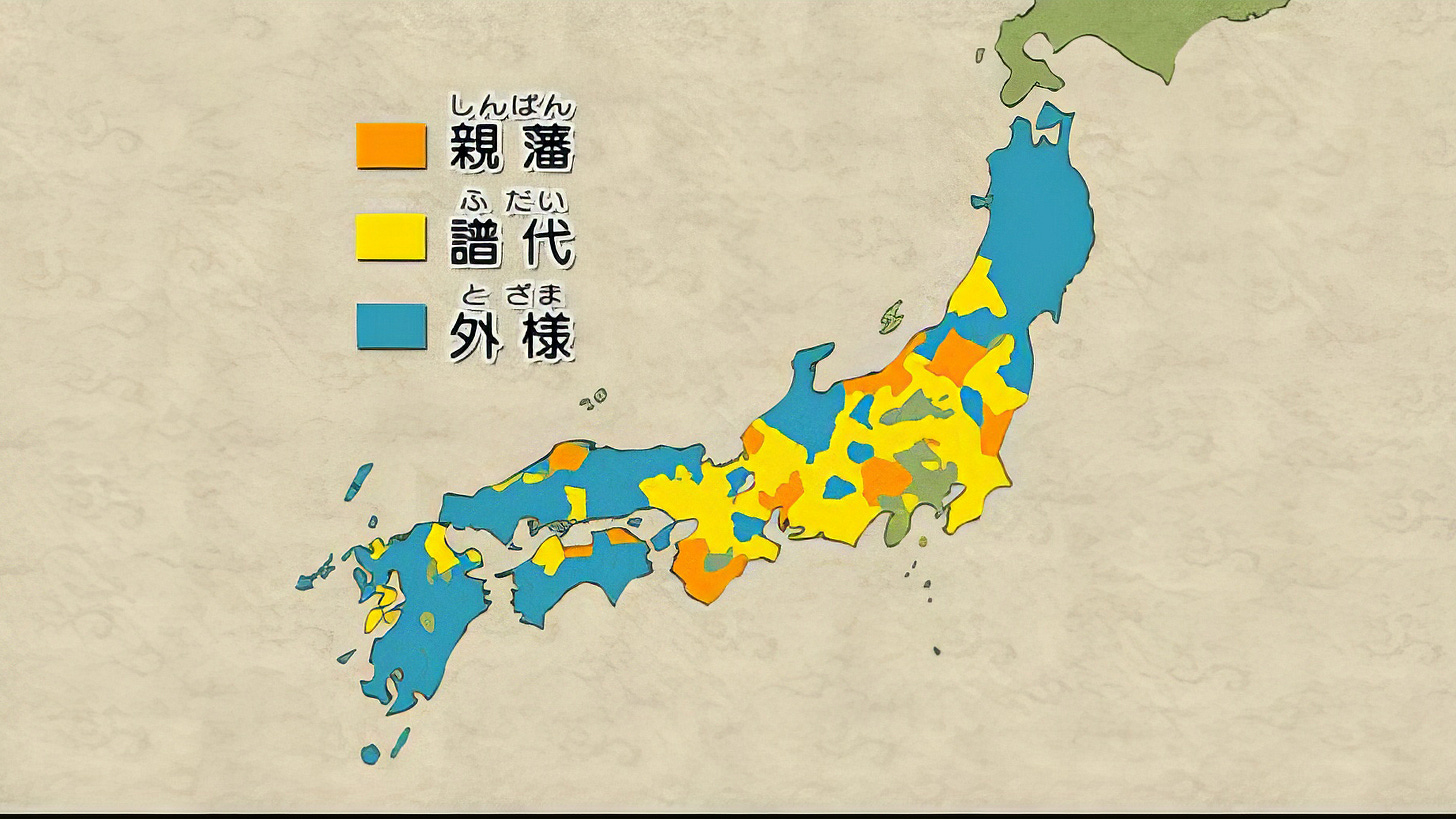

To strengthen central authority, Ieyasu categorized the powerful regional lords (daimyō) into three distinct classes:

1. Shimpan (親藩) – Tokugawa family relatives

2. Fudai (譜代) – Daimyō who had pledged allegiance to the Tokugawa before the Battle of Sekigahara

3. Tozama (外様) – Daimyō who submitted to the Tokugawa only after Sekigahara

As the diagram illustrates, despite unifying the country, Tokugawa influence was actually geographically limited. While the Tokugawa held strong control over the Kanto, Chubu, and Kansai regions, many other areas remained under the governance of the Tozama daimyō, posing a continuous threat of rebellion.

To establish a governing philosophy that would secure Tokugawa dominance for generations, Ieyasu sought the wisdom of a highly esteemed scholar—Fujiwara Seika (1561–1619), a Confucian philosopher.

Although Seika received an attractive offer from Ieyasu, he declined, considering his own age and the long-term commitment required for such a role. Some sources suggest that Seika was not particularly fond of Ieyasu, which may have influenced his decision. Instead, he recommended the most brilliant of his disciples, arranging a meeting between Ieyasu and his student.

In 1605, at Nijō Castle in Kyoto, Fujiwara Seika introduced his disciple, Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), to Tokugawa Ieyasu. Razan was only 23 years old at the time.

Despite his youth, Razan harbored a grand ambition—to establish a new governing philosophy suited for the new era.

During this time, Japan remained plagued by the constant threat of uprisings, making a strong and centralized government essential. However, this governance could not rely solely on military oppression. Instead, it needed to cultivate a unified ideology that ensured loyalty to the Tokugawa.

Razan’s mentor, Seika, was an open-minded scholar who studied a wide range of disciplines and rejected the idea of adhering to a single school of thought. However, Razan saw this approach as too lenient. Instead, he fully devoted himself to one philosophy—the teachings of Zhu Xi (1130–1200), a Neo-Confucian scholar from the Southern Song dynasty in China.

During the Song dynasty, Emperor Zhao Kuangyin (r. 960–976) had promoted civil governance over military rule, leading to a golden age of scholarship. Zhu Xi refined Confucian principles, transforming them into a structured ideology that supported governance.

Inspired by this, Tokugawa Ieyasu, impressed by Razan’s intellectual brilliance, concluded that Neo-Confucianism, with its emphasis on hierarchy and order, was the ideal philosophy for shogunate governance. As a result, Razan, at the young age of 23, was appointed as the intellectual architect of the Tokugawa Shogunate—a remarkably unprecedented role.

Razan continued to serve as an advisor for four generations of Tokugawa shōguns—Ieyasu, Hidetada, Iemitsu, and Ietsuna—solidifying Neo-Confucianism as the ideological backbone of the shogunate. His contributions were so significant that even after his death, his descendants continued to hold key positions in the Tokugawa education system, ensuring the enduring influence of his teachings.

Most importantly, Ieyasu’s decision to adopt Razan’s ideology played a crucial role in the remarkable development of Confucian scholarship during the Edo period.