Finding Beauty in Silence and Space

The Philosophy of "Ma" and "Yohaku".

Do you ever find silence or emptiness unsettling? In Japanese culture, these seemingly “empty” states are instead seen as beautiful and have historically developed as a core cultural spirit; in music, it’s the silence between notes, in conversation, it’s the quiet pause, and in painting, it’s the unpainted space known as “yohaku” (余白)—all of which reflect the aesthetic sensibility of “ma” (間), a concept that even Western designer Alan Fletcher described in The Art of Looking Sideways, saying, “The Japanese have a word (ma) for this interval which gives shape to the whole. In the West we have neither word nor term. A serious omission.”

Let’s begin by looking at a well-known destination: the rock garden of Ryōan-ji in Kyoto, a Zen garden famous for its bold use of space, where white sand represents the sea and a minimal arrangement of stones and moss evokes a landscape far beyond what’s physically present, not as mere minimalism, but as a creative void that stimulates the imagination; while ma originally means “gap” or “interval” in Japanese, in aesthetics it is more than empty space—it is a vital component that shapes culture itself.

Buddhist thought, particularly the idea that “emptiness contains abundance,” has played a major role in the formation of ma, suggesting that silence and blank space are not forms of absence but essential elements for completing a work; in calligraphy and ink painting, the untouched white space is as important as the black brushstrokes, and only through their interplay is a high form of art born, much like how Akira Kurosawa once said in an interview, “The essence of film lies between the cuts,” highlighting the importance of ma—the space between actions—as a core element of Japanese expression, showing that this philosophy lives within Japan’s broader culture.

So when did this spirit of ma take root? It truly flourished during medieval Japan, as Zen philosophy aligned more closely with the warrior class than the aristocracy, gaining momentum during the Muromachi period (1336-1573) under samurai rule, and influencing many art forms; Zen monks, protected by warriors, explored an aesthetic of “saying more with less” through ink painting, poetry, and Noh theater, leading to bold spatial experiments in temples and gardens—where blank spaces in ink landscapes came to represent mist and sky, and slow, deliberate movements on the Noh stage created haunting resonance through unspoken intervals.

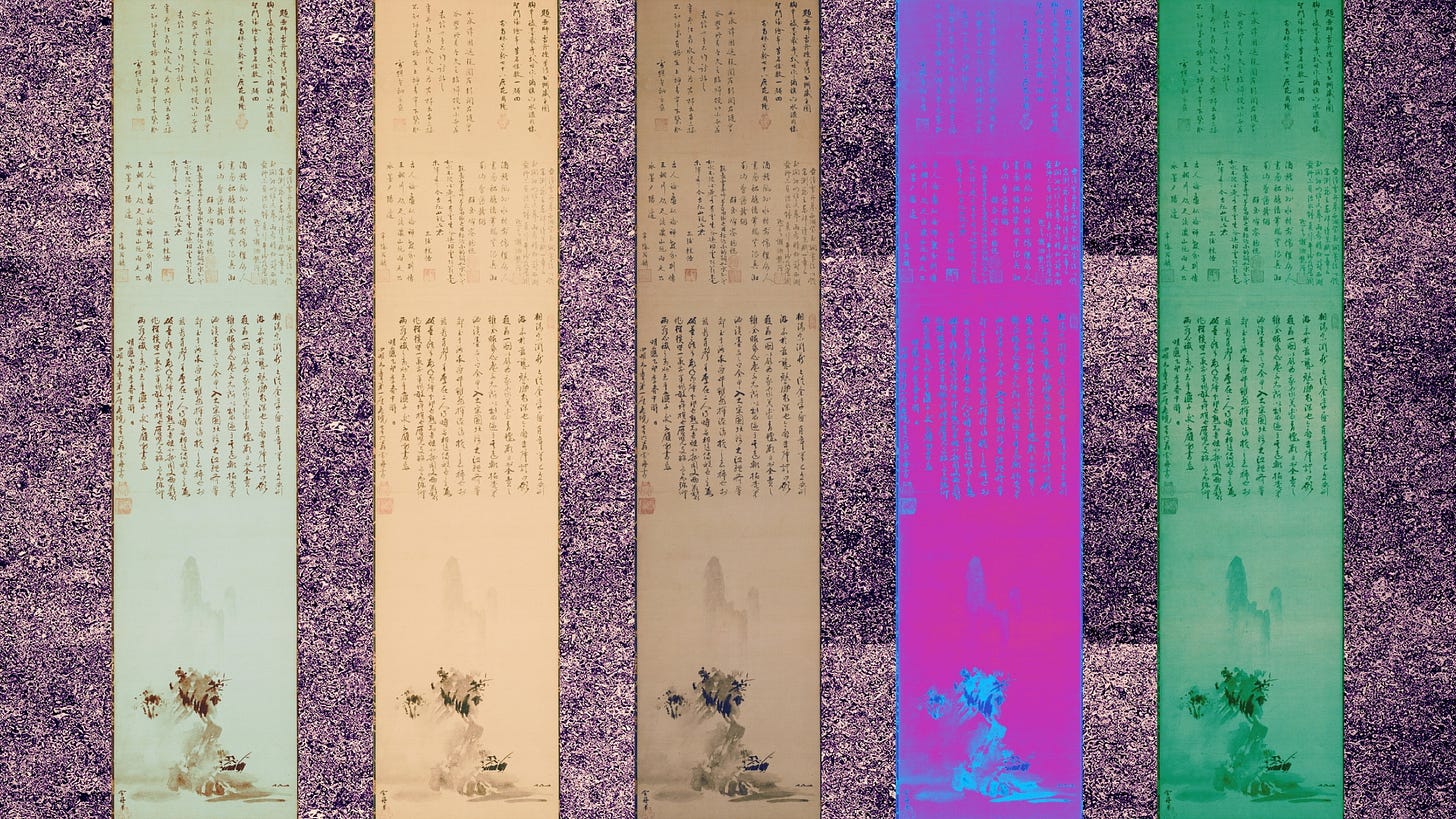

Sesshū’s Haboku Sansui (Splashed Ink Landscape), painted in 1495, is a masterpiece where blank space and Zen philosophy meet, using just a few brushstrokes to suggest mountains and trees while leaving space that evokes water and air, not merely as technique but as a reflection of his way of life; such a bold proposal of “the beauty of blankness” spread into tea ceremony and architecture, permeating Japanese culture from the medieval to early modern era, where people influenced by Zen came to prefer a moon glimpsed through clouds over one that is full and perfect.

As this unique aesthetic developed among monks and warriors, it gradually reached the common people during the Edo period, when Zen teachings began to adapt—moving away from doctrine and instead appealing to the senses—leading monks to use ink paintings and calligraphy to bring Zen closer to everyday life, and allowing expressions of ma to naturally settle into popular arts like haikai and kabuki; in the world of haiku, Matsuo Bashō captured entire worlds in 17 syllables, leaving vast space for the reader’s imagination, while in the tea room, Sen no Rikyū and his followers pursued the beauty of stillness through simplified architecture and minimalist space, which matured into the refined wabi-cha style during the Edo era.

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, a great 20th-century writer, praised the spatial beauty of Japanese architecture in his 1933 essay In Praise of Shadows (陰陽礼讃), noting how “instead of adding decorations to the wall, we recess the wall to create a tokonoma, where faint shadows cast by soft light become the highest form of adornment,” and this book remains a treasure trove of insight into Japanese aesthetics, showing how untouched space itself becomes a source of profound meaning.

Even today, this sense of ma is alive at the core of Japanese culture and continues to attract global attention; in 1978, the exhibition “MA—Space and Time in Japan” held in Paris introduced it internationally as a key concept of Japanese beauty, with architect Arata Isozaki as one of the curators, and from then on, ma became widely referenced in discussions of Japanese minimalism, influencing everything from architecture and product design to decluttering trends in everyday life—visible even in the clean spatial philosophy of Apple products.

This historical journey ultimately contributed to the birth of the Japandi aesthetic, which blends Japanese and Scandinavian design, and shows how the aesthetic of ma, nurtured in medieval Japan, has transformed with time but still resonates in the modern world; and perhaps, for us living in this high-speed digital age, it is all the more important to rediscover the value of ma, to step away from the noise and reconsider the richness of blankness, where we may find that stillness and silence have always been there—and may yet lead us toward a more meaningful life.