Cherry Blossoms and Their Changing Symbolism

History of Cherry Blossoms from Aristocrats to Samurai and the Public

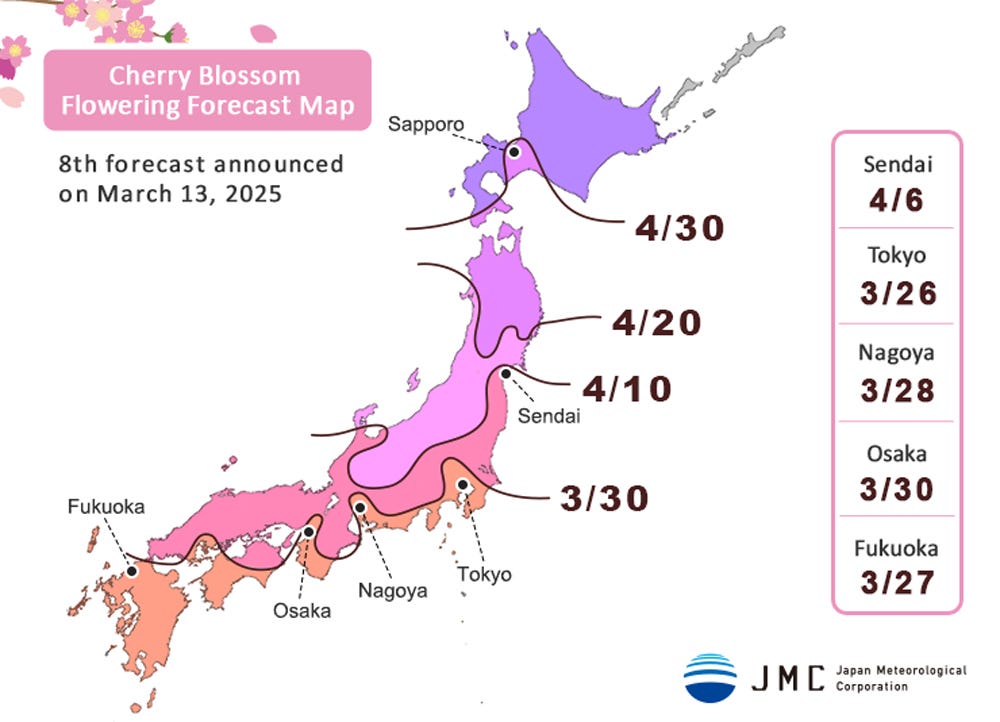

As spring 2025 approaches, cherry blossoms are beginning to bloom across Japan. In recent years, climate change has made it difficult even for Japanese people to predict the timing of sakura season (cherry blossoms). However, this year’s forecasts indicate that the blossoms will appear around the same time as usual, with no major deviations from last year.

According to predictions, Tokyo’s cherry blossoms will start blooming around March 26 and reach full bloom around April 2, while in Kyoto and Osaka, the blossoms will open around March 30 and peak around April 6–7. In Fukuoka, located in southern Japan, the flowers will begin to bloom in late March, while the further north one goes, the later the season arrives. Sapporo in Hokkaidō is expected to see blossoms opening around April 27, with full bloom anticipated in early May.

For travelers eager to experience Japan’s cherry blossoms, the key is to keep their itinerary flexible, adjusting their journey to follow the blooming sakura rather than scheduling trips based on personal convenience. To fully enjoy Japan’s sakura season, one must move according to the flowers, not the other way around.

Cherry blossoms have long been deeply embedded in Japanese arts and identity. The tradition of hanami (花見, flower viewing) is widely recognized as a long-standing cultural practice in Japan, but in the Nara period (710–794), the main attraction was not cherry blossoms but rather plum blossoms. This was due to cultural influences from Tang China, where the aristocracy admired plum blossoms, a practice that was imported to Japan. However, during the Heian period (794–1185), cherry blossoms took center stage, and in Japan, the word “flower” came to be synonymous with sakura.

The earliest recorded instance of a flower viewing banquet under the cherry blossoms dates back to 812 AD. According to the historical text Nihon Kōki (日本後紀), the emperor of the time hosted a grand hanami event in Kyoto. However, in contrast to modern hanami, these early flower-viewing gatherings were not public festivities but rather aristocratic social events. From the 9th century onward, sakura appeared frequently in waka poetry (和歌) and illustrated handscrolls (emaki / 絵巻物), reflecting the increasing significance of flower viewing among the nobility. For instance, the Kokin Wakashū (905 / 古今和歌集) and Shin Kokin Wakashū (1205 / 新古今和歌集), both imperial anthologies, contain numerous poems about cherry blossoms. Additionally, historical illustrated scrolls such as Kasuga Gongen Genki (1309 / 春日権現験記) and Heike Nōkyō (1164 / 平家納経) feature depictions of cherry blossoms. These works show that over centuries, cherry blossoms became deeply woven into the aesthetics of Japanese culture.

The symbolic significance of cherry blossoms, initially reserved for the aristocracy, gradually evolved as the samurai class gained power. With the rise of the samurai class, sakura came to represent the ethos of the samurai, eventually permeating into common society. By the Edo period (1603–1868), hanami had spread widely among the general populace, transforming sakura from a symbol of aristocratic culture into one embraced by all classes. One pivotal figure in this transition was Tokugawa Yoshimune (徳川吉宗, Shogun from 1716–1745). Yoshimune was the first leader to actively promote sakura tree planting, developing public sakura-lined avenues that laid the foundation for modern hanami culture. It was during this period that the practice of eating and drinking under the cherry blossoms became firmly established, shaping the hanami customs we know today.

Over the course of a thousand years, cherry blossoms have also been elevated into a distinctly Japanese aesthetic philosophy known as “mono no aware” (もののあはれ). This concept, difficult to translate into other languages, can be summarized as an appreciation of the ephemeral nature of beauty and life itself. Because cherry blossoms bloom for only a short time before quickly falling, they came to symbolize the fleeting nature of existence. The samurai, who lived by the sword and often met sudden deaths on the battlefield, found deep resonance in this imagery. This led to a unique philosophy among the Japanese: rather than focusing on how to live, they placed greater emphasis on how to die. This concept, closely intertwined with Buddhist teachings, was further refined by the samurai class and integrated into their way of life. Even today, this underlying philosophy continues to influence the Japanese mindset.

As Japan entered the modern era, the symbolism of cherry blossoms underwent a significant transformation, particularly as it became intertwined with militarism. During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army drew parallels between the fleeting nature of sakura and the ideal way for a soldier to die. The term “sange” (散華), literally meaning “scattering flowers,” was used as a euphemism for fallen soldiers, reinforcing the notion that death in battle was as natural and beautiful as cherry blossoms falling from the trees. This idea was further emphasized in the imagery of the kamikaze pilots, whose planes were adorned with sakura emblems. Young soldiers, given only enough fuel for a one-way mission, were encouraged to embrace their fate just as cherry blossoms did.

Following Japan’s defeat, the militaristic symbolism of cherry blossoms rapidly faded. Instead, sakura came to be associated with peace and hope, aligning with the vision of the American-led occupation forces. This shift positioned cherry blossoms as symbols of postwar reconstruction, and during Japan’s rapid economic growth, thousands of sakura trees were planted nationwide. Today, most of the cherry trees seen throughout Japan were planted during this period. Cherry blossoms were also used in diplomatic efforts, such as the gift of sakura trees to Washington, D.C., a gesture of friendship between Japan and the United States.

A major development during this time was the nationwide planting of the Somei Yoshino variety, particularly between the 1950s and 1960s. This cultivar was favored due to its rapid growth and uniform blooming, making it ideal for creating picturesque landscapes. Consequently, the majority of cherry trees seen by travelers in Japan today are Somei Yoshino. However, the widespread planting of a single cultivar has led to a new challenge: the aging of cherry trees. Cherry blossoms have a lifespan of about 50 to 60 years, and many of the trees planted during the mid-20th century are now reaching the end of their life cycle. With local governments facing financial constraints, tree replacement efforts have been slow, and infrastructure maintenance is struggling to keep pace. This means that the iconic cherry blossom landscapes that many travelers seek to experience may no longer exist in a decade if replanting efforts are not properly addressed.

Considering these historical and contemporary factors, appreciating Japan’s cherry blossoms today carries a deeper significance. Beyond their beauty, they represent centuries of cultural evolution and shifting symbolism. As we witness how the meaning of sakura has changed over time—from imperial luxury to samurai philosophy, from wartime propaganda to symbols of peace—it is worth contemplating what role cherry blossoms will play in the future. Just as sakura have adapted to the changing tides of history, their significance in Japanese society will continue to evolve. For travelers, reflecting on this transformation while enjoying hanami offers a richer and more profound experience of Japan’s cultural heritage.