Ancient Izumo Revealed Through Stunning Archaeological Finds

How Bronze Age Relics Challenge Japan’s Historical Narratives

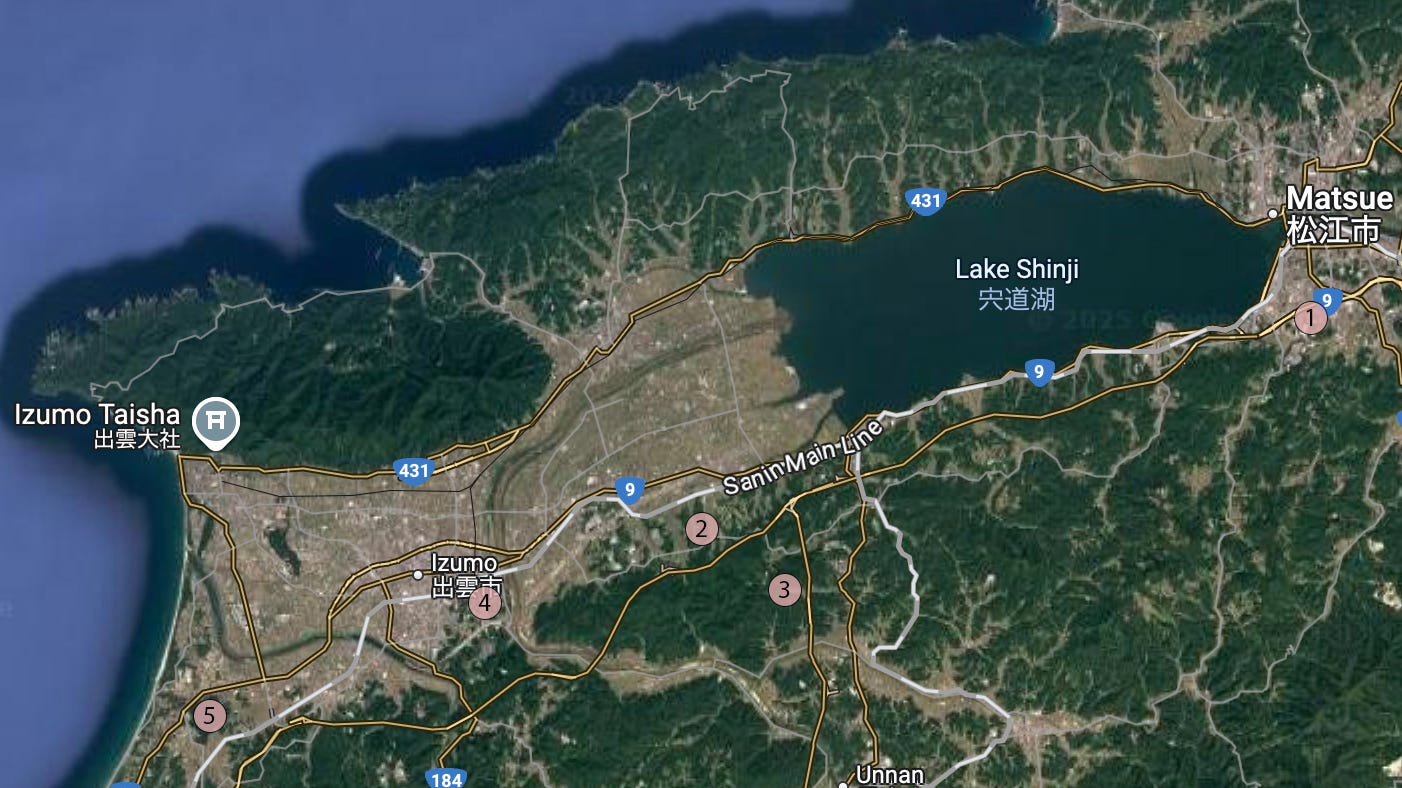

Continuing from Part I centered around Izumo Taisha Shrine, today we’ll delve into remarkable archaeological discoveries that shed new light on ancient life in the San’in region—particularly around Shimane and Tottori Prefectures along the Sea of Japan.

In 2000, pillar remains from an ancient elevated shrine were found within Izumo Taisha’s grounds, transforming mythical accounts of ancient Japan into tangible historical evidence. Around this same period, additional groundbreaking discoveries emerged from the hills surrounding what were once much larger lakes: Lake Shinji and Lake Jinzai.

Between 1997 and 2000, excavations atop Tawayama Ruins (田和山遺跡), overlooking Lake Shinji near Matsue, uncovered an extraordinary Yayoi-period settlement protected by triple moats. Typically, such Yayoi moat settlements had houses within the moats. However, Tawayama was mysteriously unique: residences were located exclusively outside its defensive moats, making it an anomaly with unknown purpose.

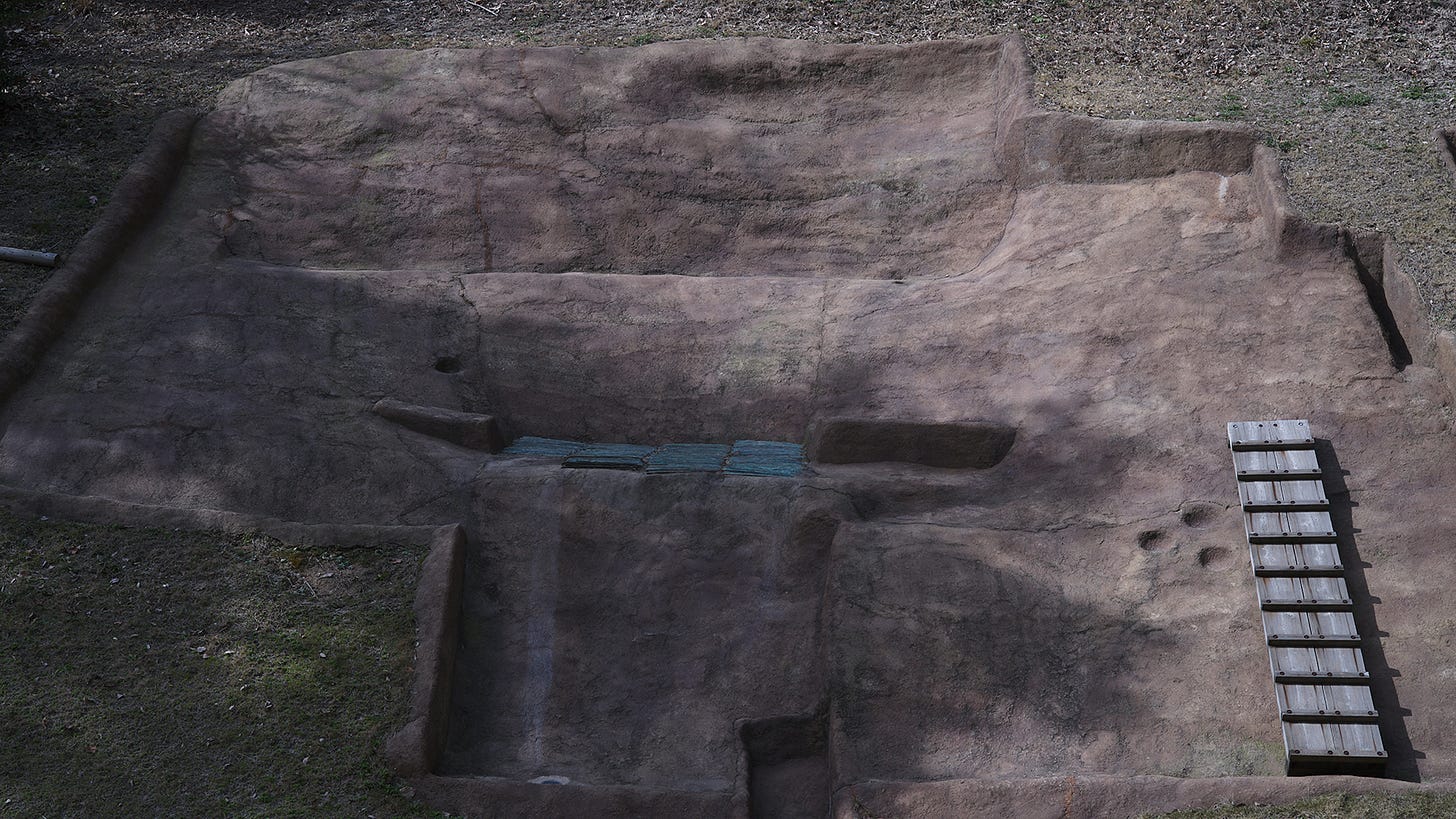

Further to the west, another discovery drastically altered our understanding of ancient Japan. At Kojindani Ruins (荒神谷遺跡) in 1984, workers constructing a farm road stumbled upon an astonishing cache of 358 bronze swords (銅剣), 16 bronze spears (銅矛), and 6 bronze bells (銅鐸)—all ceremonial objects from the Yayoi period. Notably, these bronzewares (青銅器) were not weapons but items used in religious rituals. This find was unprecedented, as previously Shimane was believed to contain few such artifacts, prompting a radical re-evaluation of Japanese prehistory.

Twelve years later, in 1996, a similar treasure trove surfaced at Kamo-Iwakura Ruins (加茂岩倉遺跡), just 3.3 kilometers from Kojindani, again during road construction. This hidden valley yielded an incredible 39 bronze bells, making it the largest single collection of such bells found anywhere in Japan. Interestingly, a forgotten ancient pathway connecting these two sites was also discovered—an old mountain trail still used by locals into the 20th century, unknowingly walking in the footsteps of Yayoi ancestors.

Analysis of the bronze objects revealed yet another surprise: the lead used in their production originated not from Japan, but from the Korean Peninsula and northern China. Intriguingly, artifacts buried side by side had different origins; some swords contained Korean lead, others Chinese. To date, the source of the copper remains unknown.

While the prevailing view holds that Japan imported most bronze objects from Korea and China, recent discoveries indicate some domestic production. Many bronze artifacts from the Izumo area bear a mysterious “X” mark, suggesting a specialized local workshop. Although the actual site of this workshop remains undiscovered, its existence seems highly probable given the abundance and consistent marking of these artifacts.

All these discoveries collectively suggest that ancient Izumo—stretching from modern-day Izumo City to Matsue—maintained robust international interactions, especially with China and Korea. Local legends even spoke of buried treasures long before archaeological confirmation at Kamo-Iwakura, indicating ancient historical truths hidden within local lore.

Nearby, on the western hills, researchers unearthed the Nishidani Tumulus cluster (西谷墳墓群), consisting of 27 burial mounds dating from the late Yayoi to early Kofun periods. Though initially recognized in 1953 when pottery was found, no one suspected the existence of large tombs until excavations between 1983 and 2018 revealed uniquely shaped tombs exclusive to Izumo. These square tombs, distinctively protruding at each corner, were identified as royal burial sites belonging to ancient rulers who governed the region.

Yet, a lingering mystery remains. Yayoi-era people typically settled in plains suitable for agriculture, not remote mountain valleys. Why, then, did Izumo’s ancient inhabitants bury ceremonial bronzeware deep in isolated hills? Examination of solar orientations at these sites showed no connection to sunrise or sunset, suggesting deliberate attempts to conceal their sacred objects.

This intriguing practice points toward ancient Chinese philosophy, specifically Taoism’s Yin-Yang theory (陰陽論). At Kamo-Iwakura, bronze bells were deliberately placed only in one of two pits—hinting at an ancient application of Taoist duality. Taoism’s founder, Laozi (老子), taught that valleys were spiritual places, inexhaustible sources of life. Such beliefs were foreign to both the earlier Jomon and mainstream Yayoi populations.

**老子【谷神不死。是謂玄牝。玄牝之門、是謂天地根。緜緜若存、用之不勤】

It seems plausible that ancient tribes from China or Korea, bringing Taoist ideas, influenced or integrated with the local Izumo people. Whether these groups were purely foreign, local, or mixed remains unknown. Evidence suggests a distinct local tribe around Izumo and a hybrid group around Matsue. Furthermore, recent discoveries increasingly support ancient legends recorded in Kojiki and Nihon Shoki as historical, not merely mythical, accounts.

What exactly happened in ancient Izumo? Why did these Yayoi inhabitants suddenly bury ritual bronze objects en masse, only to mysteriously vanish by the subsequent Kofun period?

The key lies hidden beneath Izumo Taisha Shrine itself—in the undiscovered remains of its legendary ancient elevated shrine. Revealing this structure could rewrite Japanese history, illuminating movements of unknown peoples who traveled through San’in into the Yamato region (modern-day Nara). Such revelations could profoundly challenge accepted narratives, including imperial history.

My exploration into ancient Japanese history will continue, uncovering these captivating mysteries and bringing readers closer to Japan’s extraordinary past.